The First Impression: Clear Teaching, Warm Community, and a Desire to Understand

For people who truly want to understand the Bible more deeply, Shincheonji’s Bible study program can feel incredibly convincing at first. Many former members say they were drawn in by how clear and organized the lessons seemed—especially when it came to complicated parts of the Bible like the Book of Revelation and the parables of Jesus. These teachings felt like they were uncovering secret truths that no one else had ever explained before.

One person shared how amazed they were that the SCJ teacher could answer every single question with a Bible verse—without even using notes. The teacher seemed like a “walking Bible.” That kind of confidence and clarity can be really powerful, especially when you’ve never seen that level of explanation in other churches.

In many traditional church settings, the messages might focus more on motivation or surface-level topics, which can feel disconnected if you’re someone who’s really hungry to know God’s Word on a deeper level. SCJ fills that gap by offering what feels like strong, detailed answers backed by scripture.

But it’s not just the teaching that pulls people in—it’s also the community. Early on, new students often feel a strong sense of support, encouragement, and warmth. Many describe being surrounded by people who constantly check in on them, offer prayers, and express deep care. Some later come to see this as a form of “love bombing”—a strategy meant to create quick emotional bonds and loyalty. It feels like you’re instantly part of something bigger—something meaningful and deeply spiritual.

At that stage, it doesn’t feel manipulative. It feels like family. And for many, that’s exactly what they’ve been missing.

The warmth wasn’t just kindness—it was part of a strategy to build emotional connection and trust before introducing the group’s deeper doctrines. That early bond can make it much harder to walk away later, even if you start to have doubts.

In the beginning, though, the mix of clear teaching, scripture-focused answers, and a tight-knit, supportive community is powerful. For someone searching for truth, it can feel like they’ve finally found it.

For further exploration in breakdown SCJ Bible Study framework: Testing Shincheonji’s Claims: Two Lenses, One Story

At first, many students in the Bible study feel excited and connected. But later, some realize there’s more going on behind the scenes. In most cases, the name “Shincheonji” is not mentioned at the beginning. Instead, teachers often say they’re just Bible teachers or part of a “non-denominational” group. Some even pretend to come from other churches or made-up groups.

Former members say that the name “Shincheonji” usually doesn’t come up until months later—after the student has already built strong emotional connections and feels deeply committed to the class and the people in it. By the time the name is finally revealed, students are often emotionally invested and mentally prepared to accept Shincheonji’s teachings. Because of this, many say the whole thing felt staged or planned to slowly ease them into the group.

One ex-member named Laurie, who used to be a leader inside SCJ, said that in most classes, only about half of the people are actually new. The other half are long-time members pretending to be new students. These planted members are called “maintainers” or “leaves.” Their job is to observe the new students, build trust, ask personal questions, and report what they learn to the teachers.

That way, the teacher would later mention something personal about the student during class, making it feel like the teacher had divine insight—like they were getting information straight from God. This made the teaching feel more powerful and convinced many students that what they were hearing must be true. But really, it was all part of a carefully designed method to gain the student’s trust.

SCJ uses this method to connect to people’s deepest struggles, like feeling lost, dealing with grief, or searching for a stronger purpose. They tailor the message to speak directly to those emotional needs. That’s why it often feels like God Himself is talking to you through the lessons.

From Shincheonji’s own point of view, this way of slowly revealing their identity is not deception, but a teaching strategy. They believe it’s important to first build a strong foundation—to teach people how to understand the Bible’s parables and figurative language—before telling them where the teachings come from. Students are told to listen humbly, reflect deeply, and test everything against the Word, before they know the group’s name or that the teacher is connected to Schincheonji.

They say this method is like watching a movie or TV show. You don’t want the spoilers too early, because it ruins the anticipation. In the same way, SCJ builds up to the big reveal by using repetition, subtle clues, and “Easter eggs”—hidden hints dropped throughout the lessons.

Eventually, all of this leads to the big reveal, what they call the “testimony.” This is the moment when everything is “unveiled,” and students are told the full truth: that the “New John,” also known as the “promised pastor,” is Lee Man-hee, and that he is the only one who has received the open word directly from Jesus. They believe that when this testimony is shared, students will suddenly realize that all the puzzle pieces fit together and that Shincheonji is the truth.

But SCJ also knows that if they came out right away and said, “This is Lee Man-hee, and he is the Messiah you need for salvation,” most people would probably walk away. So, they wait—until students are more ready to hear it and more likely to accept it.

This strategic pacing is meant to keep people from being shocked and leaving too soon. But for many former members, this feels like a trick. They say it’s manipulative, not spiritual. Teachers often avoid answering certain questions—especially if the student already knows what to ask. That’s a red flag to many people. It shows that some information is deliberately hidden until the “proper time” in the class.

Another issue is consistency. Not every SCJ Bible class is the same. Different teachers may use different names for the course. Different tribes may use different strategies or teaching styles. Over time, this can lead to confusion—almost like a “telephone game,” where the message changes slightly as it gets passed on.

Now, it’s true that SCJ has many of their lessons available on YouTube, and Lee Man-hee has published books that are meant to track what the official teachings are. Many members and ex-members also take detailed notes during the classes. These materials can help keep a record of what is being taught and are important tools for watching doctrinal consistency over time.

But even with these public materials, many former members have witnessed doctrinal change—moments when the teachings had to shift because they didn’t match reality or the fulfillment SCJ expected. In other words, when a prophecy failed to come true, the doctrine was changed to explain it away.

This kind of shift isn’t just “spiritual growth.” Critics and ex-members say these changes are often done to protect the group’s image. Like many other high-control groups, Shincheonji tends to cover up doctrinal changes, sometimes rewriting history or avoiding open conversations about why the change happened. This is why having records—like class notes, official videos, and published materials—is so important. They help people see the development of the doctrine and detect gaslighting or manipulation.

A major example was during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many members started noticing clear changes in the teaching. The fulfillment that SCJ had claimed would happen in real life did not match what was going on in the world. The leadership then began to shift the teachings to fit the new reality. As a result, many members left, feeling betrayed and confused.

This shows why it’s crucial to stay alert and watch for doctrinal change—especially when it’s used to justify failure or cover up unfulfilled prophecy. It also reminds us that no matter how spiritual or organized something looks, we need to ask: Is it still saying the same thing? And if not—why did it change?

Some ex-members, like Laurie, say they noticed what they call “irrational doctrine” or “manipulative tactics.” This supports the idea that SCJ may reinterpret their teachings when needed to stay relevant or avoid looking wrong.

There’s also a lot of pressure to evangelize. In SCJ, bringing in new students—called “fruit”—is seen as essential. Members are taught that “saving souls” is the most important thing in the world and that God’s will is to save lives by any means possible. This makes people believe that the ends justify the means; they even have a name for it: the “wisdom of hiding”. In other words, it’s okay to withhold information or be vague, because in their minds, they’re doing it for God.

Inside the group, there’s a strong system of internal monitoring. People are encouraged to report on each other. “Strong members” are supposed to help or guide “weak members”, especially if someone starts to doubt or question the teachings. There’s a lot of pressure—emotionally and spiritually—to stay in line.

This pressure comes in the form of fear and guilt: fear of the outside world, fear of losing salvation, fear of being punished, fear of leaving and being cut off from friends. These fears make it very hard to think clearly or walk away.

Many former members say they were told their life before SCJ was “really bad.” This message is repeated so often that people start to believe it. So even when things inside SCJ are difficult, members convince themselves that it’s still better than what they had before.

By the time someone learns the full truth about Shincheonji—about who they really are, what they really believe, and how deeply the structure is designed to control rather than simply teach—it often feels like waking up from a very well-produced story. For many, the emotional bond has already been formed, the tests passed, the sacrifices made. And that’s exactly why the reveal comes so late.

The delay isn’t accidental. It’s strategic. It’s about shaping someone’s understanding and loyalty before giving them the full picture. And when questions are finally asked, the answers often come too carefully, too vaguely—or not at all.

What started as a journey for truth, clarity, and purpose slowly becomes a world of hidden systems, staged relationships, controlled environments, and shifting doctrines. Doubts are labeled as weakness. Outside voices are dismissed as poison. Loyalty becomes tied to identity, and walking away starts to feel like betrayal—not just of the group, but of God Himself.

One big reason why many people find SCJ’s Bible study so convincing is the way they explain the Bible using figurative meaning. They don’t just read it literally—they say the whole Bible is a book of parables and prophecy, filled with hidden messages that were sealed until the right time. And that time, they say, is now.

According to SCJ, only one person—Lee Man_hee, who they call “New John” or the “promised pastor”—has received the open word directly from Jesus. They teach that this open word is the only way to understand the true meaning of the Bible’s prophecies, especially in Revelation.

At first, these teachings may sound deep and mysterious, and for many, they offer answers to questions they’ve had for a long time—especially when traditional churches didn’t have clear explanations. But over time, some students start to notice that the explanations are not always consistent and don’t always match what the Bible says when read in full.

For example, SCJ teaches that in the story of Genesis 1, the “animals” represent people, the “garden” is the first church, and the “snake” is not a real animal but a spiritual being. These ideas are presented as the “spiritual meaning” of the story. To someone who’s struggled with the literal version of the Bible—especially parts that seem hard to believe—this kind of teaching can feel like a solution. It appears to answer confusing questions while still sounding biblical.

This figurative method can also feel very exciting. It makes students think they’re learning secrets that no one else knows. SCJ compares this to solving a puzzle or watching a TV show with hidden clues that only make sense at the end. But this style of interpretation is not unique to Shincheonji.

In fact, it’s very similar to the “creative liberties” taken in TV shows and movies when adapting biblical stories, or even other popular works like books or anime. Just as showrunners adapt these sources for the screen by adding new scenes, changing the storyline, or inventing details that are not in Scripture. This is often done to make the story feel more dramatic, modern, or emotionally powerful. But the downside is, these changes can distort the truth, even if they sound biblical. This can lead to criticism when the adaptation is seen as disloyal to the source material or when key elements are changed to push a specific narrative or social agenda.

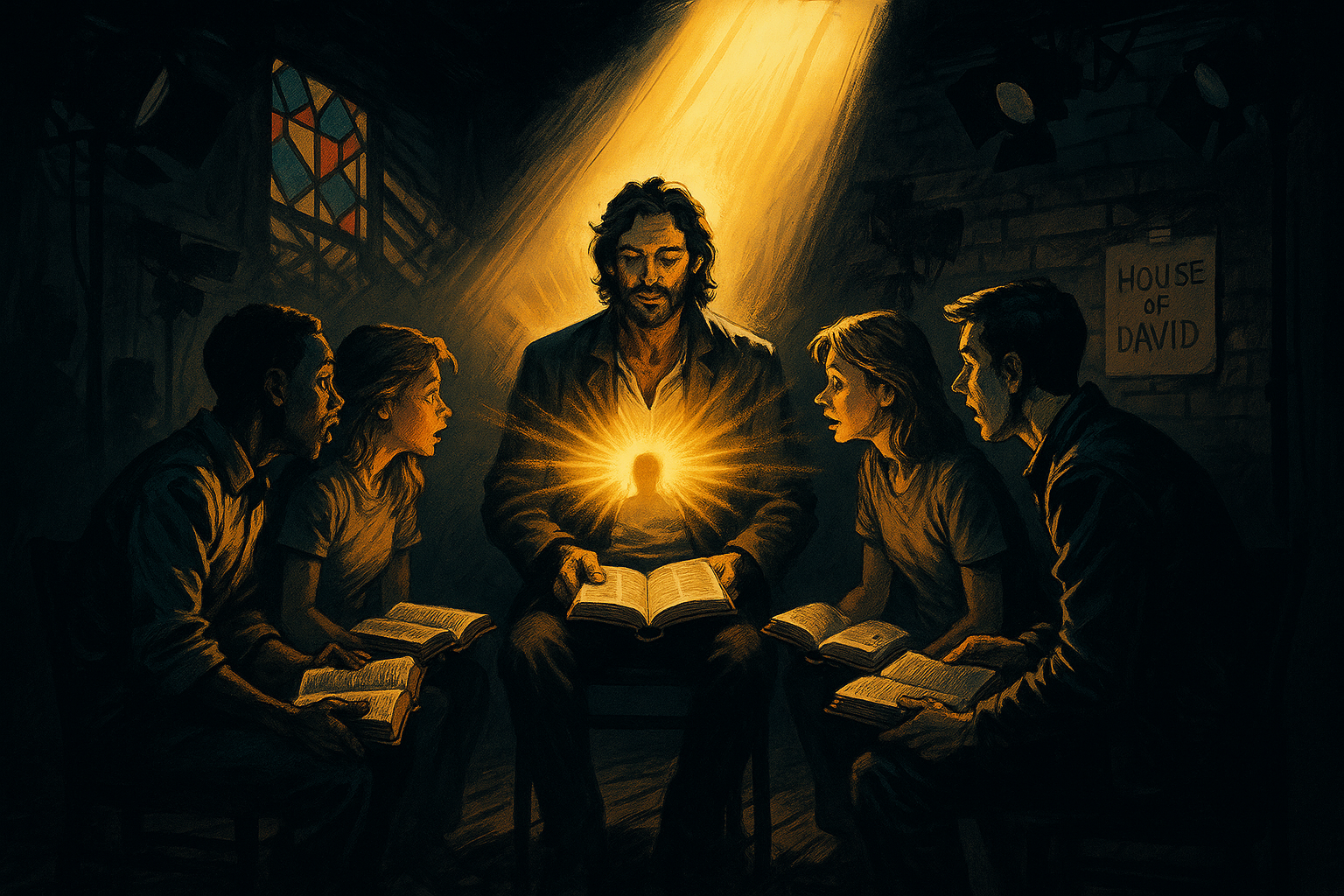

For example, in Amazon’s House of David, David is shown as a bastard child, and the show adds emotional backstory—like him killing a lion out of revenge—which is not in the Bible. It also changes how characters like Saul behave, and skips important lines, like David’s speech about God’s covenant before fighting Goliath.

Other shows, like The Chosen, also add dialogue and dramatize scenes that are not found in the Bible word-for-word. For instance, Jesus saying, “I am the law of Moses” is a line taken from the Book of Mormon, not the Bible. Even if the show’s intention is to help modern audiences connect with the emotional weight of the characters, creative liberties can blur the line between truth and dramatization. Sometimes convey biblical truths through character development, viewers need to stay alert: emotion alone doesn’t equal accuracy. Even when the message feels true, it’s important to check whether the words match Scripture.

Pastor Levi Lusko, in a The Chosen behind-the-scenes interview, points out how emotional power can enhance storytelling—but reminds us that when it comes to Scripture, faith must be grounded in truth, not just feeling.

And Rede Record, a major Brazilian TV network, has created lengthy biblical telenovelas that—because of their extended episode count—rely heavily on invented subplots, fictional characters, and romantic storylines intertwined with biblical events. Some of these shows even assign specific backstories or roles to Jesus’ siblings that are not found in Scripture. These embellishments, while dramatic, can easily distort the viewer’s understanding if not grounded in the full biblical context.

That’s why the Bible teaches us to use clear verses to interpret unclear ones. When one passage is symbolic or harder to understand, we look to other parts of Scripture that explain the same concept in a more direct way. As it says in 2 Peter 1:20, “No prophecy of Scripture comes from someone’s own interpretation.”

But when SCJ teaches, they often pick verses that fit their narrative—what people call “cherry-picking.” This means they’ll pull certain Bible verses out of context and string them together in a way that supports their claims, without showing the full passage or the bigger picture. It’s like taking clips from a movie and re-editing them to tell a new story that wasn’t originally there.

That’s why it’s so important to handle unclear verses carefully. The Bible doesn’t contradict itself. When something is not clear in one place, we are meant to look elsewhere in Scripture to understand its meaning—not build an entire doctrine on one isolated passage.

Isaiah 28:10 reminds us: “Precept upon precept, line upon line, here a little, there a little.”

This isn’t just poetic—it’s a key to understanding Scripture in context. Each verse works like a puzzle piece in a larger picture. The Bible interprets itself.

One helpful tool for this is the structure known as chiasmus, found throughout the Bible, especially in the Psalms, the teachings of Jesus, and Revelation. Chiasmus presents thoughts in mirrored pairs—like A-B-C-B′-A′—drawing attention to a central point while connecting ideas through internal parallels.

For example, Matthew 23:12 follows a chiastic form: “Whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be exalted.”

This reversal not only teaches a principle but emphasizes the truth by reflecting it back on itself.

In Revelation and Old Testament prophecy, chiasmus helps clarify symbolic language. If one verse mentions “lampstands” symbolically, another verse elsewhere will help explain what they are—like Revelation 1:20, which says, “The seven lampstands are the seven churches.”

It’s not guessing—it’s Scripture interpreting Scripture.

This is why when SCJ pulls a verse out and gives it a new meaning, without aligning it with the rest of the Bible, it leads to confusion. SCJ often discourages reading “outside” material or questioning their interpretation, but the Bible was written to be tested and understood in full. 2 Timothy 3:16–17 teaches that “All Scripture is God-breathed… so that the servant of God may be thoroughly equipped.” Not selectively equipped.

So instead of cherry-picking verses to prove a point, we’re meant to follow the full flow of Scripture—its cross-references, patterns, and literary designs like chiasmus. These tools weren’t invented by modern readers—they were built into the Bible by design, to help us know the truth from every angle.

In the same way that a TV show might reshape a character’s background to make the message more dramatic, SCJ reshapes the Bible’s message to make it feel exclusive and new. But the danger is: unless someone is already grounded in Scripture and knows the full story, it’s easy to believe these added meanings as truth—because they sound convincing and are connected to real Bible verses. Over time, these small changes can shift the message completely.

For example, SCJ teaches that the “144,000 sealed” are a real group of people today. They say these are members of Shincheonji who must be sealed and evangelize to reach salvation. This is not a new idea, but a new spin on old themes—presented in a way that seems exclusive, like only those in SCJ have access to heaven.

Also, SCJ says that only one person, the “promised pastor,” can explain the Bible correctly. This kind of setup creates what critics call an “echo chamber”—a space where only one voice is allowed, and all outside views are shut out. People are told not to question or look elsewhere because other views are “slander,” “poison,” or even “persecution from the devil.”

This method is very similar to tactics used by other high-control groups or cults. They often create an “us vs. them” mindset, where outsiders are dangerous and the group is the only safe place. When this happens, even honest questions or outside information are seen as a threat.

Many people stay in SCJ because the leaders seem sincere. They really believe they are doing God’s work. But sincerity is not the same as truth. People throughout history have been sincerely wrong—believing things that later turned out to be false. That’s why it’s so important to check if something is really from God, even if it feels right.

As 1 Thessalonians 5:21 says, “Test everything; hold fast what is good.” And in Acts 17:11, the Bereans were called “noble” because they examined the Scriptures daily to see if what Paul said was true. That’s the model we’re supposed to follow—not blind loyalty, but honest examination.

And that’s why SCJ’s Bible study feels so powerful: because it mixes Christian theology with their own teachings. To someone who hasn’t studied the Bible deeply, it’s hard to tell where the true parts end and the added interpretations begin.

In the end, it’s not just about knowledge. Many ex-members say the thing that pulled them in the most wasn’t just the figurative teaching—it was the love bombing, the sense of belonging, and the feeling of being part of a chosen group. SCJ tells people they’re privileged to receive hidden truth, and that’s a powerful emotional hook. For people who feel lost or alone, that promise of special knowledge and salvation can be enough to silence their doubts—even when something doesn’t feel quite right.

To really understand what the Bible is saying, it’s important to look at the full context—not just one verse here or there. That means we have to take time to learn how the Bible was written, who it was written to, and why it was written in the first place.

The Bible isn’t just one book—it’s actually a collection of many books, written over hundreds of years by different people in different places. Some parts are poetry, some are letters, others are prophecies, laws, or historical stories. Each section uses different writing styles or literary genres, and if we miss that, we might misunderstand what the Bible is actually trying to say.

A lot of the Bible was originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. These ancient languages are different from English or Korean today. They had different meanings, expressions, and culture behind the words. So something that made perfect sense to a first-century reader might not be obvious to us in the modern world with phones, movies, and social media shaping how we think.

For example, the Book of Revelation uses a complex literary style that’s very symbolic. Scholars have found things like chiastic structures in it—this is a writing pattern where ideas are repeated in reverse order like A-B-C-B’-A’. It’s used to highlight the central idea in the middle. Revelation also uses parallelism, which means saying similar ideas in slightly different ways right after each other. These patterns were very common in the ancient world, especially in Hebrew and Greek writing.

Read more about this topic: Closer Look Initiative – Christianity Bible.

Examine the chiastic structures of the book of Revelation.

Revelation also has parts that feel like a drama or stage play. There are heavenly scenes, characters speaking to each other, and dramatic lines that feel like messages being delivered in a theater. For example, the chorus of heavenly creatures in Revelation 4:6–8 and the huge crowd shouting praise in Revelation 7:9–10 create a dramatic, emotional experience. These parts make Revelation feel vivid and intense, almost like a cosmic play.

Some scholars believe that Revelation reflects the influence of Greek tragedy—not because John was copying Greek theater, but because he lived in a Hellenistic culture, where people were familiar with that kind of storytelling. So, the emotions, imagery, and dialogue might reflect that background. That’s important to know, because it helps us read Revelation the way the first readers would’ve understood it.

Now here’s something really fascinating: Revelation might actually be a retelling of the battle of Jericho from the book of Joshua chapter 6. This isn’t just a random comparison—it’s what’s called typology, where something in the Old Testament foreshadows something bigger in the New Testament. It shows that God has a pattern—a consistent way of working across time.

Here are some amazing examples:

- In Joshua 5:13, the commander of the Lord’s army shows up with a sword. In Revelation 1:16, Jesus appears to John with a double-edged sword coming from His mouth.

- Jericho was a wicked, rich city that stood against God (Joshua 6). In Revelation, Babylon the Great is also shown as a wealthy, evil city (Revelation 18:2).

- In Joshua, Rahab, a woman with a shameful past, was marked by scarlet and saved by faith (Joshua 2). In Revelation, there’s a woman in scarlet too (Revelation 17:3–5), but her story is tied to judgment and redemption.

- Before the battle at Jericho, Joshua told his people to purify themselves (Joshua 5). In Revelation, Jesus tells the seven churches to repent and be spiritually ready (Revelation 2–3).

- Joshua sent two spies who were saved after three days (Joshua 2). Revelation talks about two witnesses who are raised from the dead after three and a half days (Revelation 11).

- In Jericho, they blew seven trumpets on the seventh day, and the walls came crashing down (Joshua 6:4). In Revelation, seven trumpets lead to judgments, and the final trumpet announces the fall of Babylon (Revelation 11:15, 18:2).

- Joshua told Rahab’s family to “come out” before the city was destroyed (Joshua 6:22). In Revelation, a voice from heaven says, “Come out of her, my people” before Babylon falls (Revelation 18:4).

- Joshua led Israel across the Jordan River into the promised land (Joshua 3). In Revelation 22, Jesus leads His people across the river of the water of life into the New Jerusalem.

Watch more videos and discover Jesus in every story from Watermark Gospel.

Read more about this topic: Closer Look Initiative – Christianity Series.

When you look at all of this together, it’s clear that God has a pattern. He’s telling one big story, not just random separate events. It shows that when we understand literary structure, history, and the spiritual meaning behind the words, we can read the Bible the way it was meant to be read.

But here’s why this matters so much: if we don’t understand the full context, it becomes easier for someone to twist the meaning—even using the Bible to say things it never meant. That’s why it’s so important to compare scripture with scripture, look at the original purpose behind each book, and be careful of groups or teachers who only show one side of the story.

When people don’t have this kind of grounding, they can easily accept teachings that sound biblical—but are actually distorted. That’s why studying the Bible deeply and honestly is one of the best ways to know the real truth—and to tell the difference between God’s Word and someone else’s version of it.

In Shincheonji’s Bible study, there comes a point when they start talking about something called the “physical fulfillment of prophecy”. This is a very big idea in SCJ. They believe that the prophecies in Revelation have already been fulfilled—not just spiritually, but in real life, in a physical place, through real events that already happened.

They say that these events were fulfilled in a small town in South Korea called Gwacheon, and that it all took place through the life and ministry of Lee Man-hee, the leader of SCJ. This is where the “testimony” becomes central. According to SCJ, Lee Man-hee is the witness who saw everything happen. And because he saw it, they believe he is the only one who can explain what the prophecies mean.

The “evidence” they use to support this mostly comes in the form of narrative storytelling—connecting Bible verses to real people, specific dates, and events in SCJ’s history. They show photos of large gatherings, like the 1995 event where they say the 12 tribes were established at Suwon Public Stadium, or the 2019 100,000 graduation ceremony.

These visuals are shown as “proof” that the prophecy was fulfilled, and that Revelation has already come true “in reality.” For people who are emotionally connected to the teachings, this can feel like strong confirmation that SCJ’s message is real.

But here’s the issue: there’s no way to actually verify these claims using independent, outside evidence. Former members and critics point out that the “proof” is not objective. It wouldn’t hold up in a court or academic study. It relies almost completely on what SCJ calls “testimony”—basically, Lee Man-hee saying that he saw it happen, and the group believing it based on that.

So what makes this feel convincing?

It’s not really the evidence itself. It’s the fact that by the time students hear this part of the teaching, they’ve already been through months of Bible study. They’ve already spent a lot of time, energy, and emotions on learning SCJ’s interpretation. They’ve built friendships, passed tests, and maybe even been “love bombed” with care and attention. They’re emotionally invested.

They’ve also been told that the SCJ way of reading the Bible is the only true way, and that Lee Man-hee is the only person who can interpret it correctly. By this point, it’s very hard to question what’s being presented—because to doubt the teaching feels like doubting the Bible itself.

And if someone does have doubts, those are often dismissed as “the work of the devil” or a sign that they’re spiritually immature or “not ready.” This creates an environment where people feel pressure to agree, even if something doesn’t feel right deep down.

This is why the idea of “physical fulfillment” can be so powerful—not because it’s been proven, but because people have been primed to believe it through long-term teaching and emotional pressure.

And that’s dangerous. Because once someone believes that one man’s interpretation is the only valid one—and that it’s already been fulfilled in a place they can’t verify—it becomes almost impossible to question or investigate. It puts all the authority into the hands of one person’s “testimony,” without any real checks or outside witnesses.

It’s important to remember that real truth doesn’t fear examination. If something is truly from God, it should be able to stand up to questions, to fact-checking, and to testing. But when a group only offers internal “proof” and discourages outside research, it’s a sign that something might not be as solid as it seems.

This video provides a chilling guide on how to become a cult leader, detailing manipulative tactics such as deception, love bombing, control of behavior, thoughts, and information, and inducing fear and dependency in followers. It highlights the disturbing power dynamics and psychological manipulation used by cult leaders.

One of the things that sounds really good at the start of Shincheonji’s Bible study is the idea of discernment. Students are encouraged to think carefully, ask questions, and test what’s true or false. SCJ even says this is just like what the Bereans did in Acts 17:11—checking the Scriptures to see if what they were taught was right.

They also warn students not to add to or take away from Scripture (Revelation 22:18–19) or “do not go beyond what is written” and tell them to “test every spirit” (1 John 4:1). This sounds very biblical. It gives the impression that SCJ wants people to be serious about finding the truth—not just following feelings or opinions, but checking everything against God’s Word.

In the beginning, that message makes students feel like they’re part of something thoughtful and spiritually responsible. You’re told: “Don’t just believe your pastor or your church. Let the Bible interpret the Bible.”

But over time, something changes.

Once students are deep into the months-long SCJ study program—sometimes for six to nine months, including hard tests—the atmosphere shifts. The encouragement to ask questions and test the teachings starts to fade.

Instead, students are told that any outside teaching or opinion is poison. People who speak against SCJ are said to be working with Satan or part of Babylon, which they claim is full of false teachings. Even reading other perspectives or visiting Christian websites is said to be dangerous or a way to be “spiritually polluted.”

SCJ often uses dramatic language like “the maddening wine of adultery” from Revelation 17–18 to describe other teachings. It creates fear around learning from anyone outside their group.

And that’s the irony.

At the beginning, students are taught to test everything, to be humble, and to listen carefully to Scripture. But after they’ve accepted SCJ’s teachings, that same testing and humility is not encouraged anymore—especially if it leads them to ask hard questions about SCJ itself.

People are told: “You’ve already found the truth. Don’t let anyone take it away.” But that’s not the same attitude they had when someone was questioning their old church or pastor.

Here’s what makes it even harder: SCJ teaches that the Bible was sealed until one person—Lee Man-hee, the New John—received the open word. Students are told that no one else in history could understand the Bible properly until now. So once someone accepts that idea, it becomes almost impossible to think differently. It’s like every other explanation automatically becomes “wrong” or “from the devil.”

And when someone from the outside tries to explain the Bible differently, SCJ usually doesn’t want to listen. They say things like, “That’s just human interpretation,” or “They haven’t seen the fulfillment.” But that’s strange—because when SCJ was explaining their teachings in the beginning, they wanted people to listen and think deeply.

So now it becomes a one-way street. SCJ expects others to take months to understand their teaching. But they don’t give others that same patience or openness in return.

This is how the group creates an “us vs. them” mindset.

SCJ teaches that the rest of Christianity is Babylon, filled with man-made doctrine. Only SCJ, they say, has the seed of God and the true interpretation. Anyone outside is either misled or working against God—even if they love the Bible and follow Jesus.

But here’s a hard and honest question: What if SCJ is wrong? If they are adding to or taking away from the Bible, just like they say Babylon is doing, then by their own teaching, they would also be under the same curse and judgment (Revelation 22:18–19). If Lee Man-hee is not truly sent by God, then all the warnings SCJ gives about false teachers would apply to them.

That’s why we need to be careful.

When a group claims to be the only source of truth on earth, we should always ask: Can it be tested? Can it be questioned? Can it stand up to Scripture, history, and reality? Because if it can’t—then it’s not truth. It’s control.

This kind of shift—from open-minded learning to rigid loyalty—isn’t just a spiritual issue. It’s also psychological. A famous study by psychologist Solomon Asch showed how people will often go along with a group’s opinion, even when they know it’s clearly wrong, just to avoid standing out. This is called conformity—and it helps explain why even thoughtful, discerning people can end up silencing their doubts when they’re surrounded by a strong, confident group that insists it already has the truth.

The classic fairy tale The Emperor’s New Clothes tells the story of a ruler convinced by tricksters that he’s wearing magnificent garments—visible only to the wise and worthy. Fearing judgment, no one admits they see nothing. Ministers, advisors, and citizens all nod along, affirming what isn’t real. It’s not until a child—free from fear and flattery—shouts, “But he isn’t wearing anything at all!” that truth pierces the illusion.

This story perfectly mirrors how Shincheonji (SCJ) draws people into its belief system.

“If You Don’t See It, You’re Not Spiritual Enough”

At the heart of SCJ teaching is the idea that only one person—Lee Man-hee, also called the “Promised Pastor” or “New John”—has received the “open word” directly from Jesus and can explain the Bible’s true meaning. In fact, SCJ claims:

“The one who speaks on behalf of Jesus must be known in order to come to Jesus.”

And again:

“There is no salvation except through the pastor promised by Jesus.”

It goes further. On page 399 of The Creation of Heaven and Earth, Lee Man-hee claims:

“I am the savior… I am creating the kingdom of heaven and eternal life.”

Students are taught that rejecting this “one who is sent” is the same as rejecting Jesus Himself:

“When someone disobeys the one whom God has sent, he is in reality disobeying God and Jesus.”

This is where the illusion begins.

“Everyone Around Me Believes It… So It Must Be True”

Much like the emperor’s ministers who pretended to see invisible clothes to avoid seeming unworthy, SCJ members are surrounded by long-time believers (“maintainers”) pretending to be students. Their job is to build trust, ask personal questions, and mirror belief. This creates a room full of people nodding in agreement—even if some secretly have doubts.

But no one wants to be the one to question. Because if you don’t “see” the fulfillment, or if you’re confused by the interpretation, the problem isn’t with the doctrine—it’s you. You’re told you’re not “spiritual enough” or “humble enough” yet.

This is the illusion: The more you pretend to understand, the more you’re praised as chosen.

The “Child” Who Speaks Up

In Andersen’s story, the lie only breaks when someone outside the pressure—a child—points out what’s obvious. In SCJ, this “child” moment often comes from a friend, former member, or a moment of deep reflection, where someone finally says:

“Wait. This doesn’t sound like what Jesus taught in the Bible.”

Like the emperor, many SCJ students don’t lack intelligence—they’ve been caught in a system that punishes doubt and rewards conformity.

Biblical Warning

The Bible warns us about those who claim exclusive access to salvation:

“Watch out that no one deceives you. For many will come in my name…” (Matthew 24:4–5)

“If anyone says to you, ‘Look, here is the Christ!’ or ‘There he is!’ do not believe it.” (Matthew 24:23)

“Test the spirits to see whether they are from God.” (1 John 4:1)

Truth doesn’t require fear, secrecy, or a single human gatekeeper. If someone claims that you must go through them to get to Jesus, that is a massive red flag.

Truth Doesn’t Need Illusions

In The Emperor’s New Clothes, the deception ended when one voice broke the silence. Likewise, former SCJ members are now stepping out and speaking up—not out of hate, but out of love for truth.

Because real faith doesn’t require pretending. Real truth doesn’t manipulate. And real salvation doesn’t wear a costume.

Let’s start with a picture.

Imagine spending a long time in a room where there’s a strong, constant scent—like hair oil, incense, or air freshener. When you first walk in, it’s all you notice. But after a few hours, the smell seems to fade. It doesn’t go away—you just stop noticing it. Your senses have adjusted. It’s now part of the background.

Or imagine working for hours on a paper, art project, or piece of code. After a while, your eyes go numb—you stop seeing the mistakes. You’ve looked at it for so long that you lose perspective. You’re too deep in to notice what’s wrong.

This is more than tiredness. It’s a real psychological effect: prolonged, intense exposure to one system of thought can cause you to lose your critical distance. You no longer question it, not because you fully agree—but because you’ve stopped seeing the alternative.

This is what many former members describe happening inside Shincheonji’s Bible study program.

The course is demanding—long classes, often after work or school, repeated tests, memory drills, and a strong push to “endure to the end” in order to “be the overcomer” and be saved. This intense routine can lead to exhaustion or sleep deprivation, which weakens your ability to think clearly. Over time, you stop evaluating what you’re being taught—you’re just trying to keep up.

This is where desensitization sets in.

You’ve been in the room so long, you no longer smell the heavy scent. You’ve heard the doctrine repeated so many times, it just sounds normal. Critical thinking gets dulled. The very tools you were given in the beginning—discernment, reflection, and testing the spirits—are now turned off when it comes to questioning SCJ itself.

Instead, any outside perspective—no matter how biblical or well-meaning—is labeled as “human interpretation,” “guesses,” or even “poison.” You’re told that listening to other views will “pollute your heart,” pull you away from God, and ruin your spiritual growth.

This fear-based filter creates an echo chamber: a closed system where the only voices allowed are those that already agree. Doubts are shut down. Questions are redirected. And slowly, SCJ is seen not as a path to truth, but as the only source of truth on earth.

And when that’s the only voice you’re allowed to hear, even free will becomes blurred. Are you choosing to believe the teaching—or are you simply unable to choose otherwise because you’ve never been shown another way?

This is where the analogy deepens.

Sometimes, the only way to see the difference is to step outside the room.

Open a window. Step outside for a breath of fresh air. Read the Bible alone. Talk to someone who doesn’t speak in metaphors. Watch a Christian video that doesn’t mention New John or sealed tribes. Even a short break can make the scent in the room hit you all over again when you walk back in.

You might notice things that were always there but had become invisible—inconsistencies, pressures, or assumptions that you once accepted without question.

And this brings us to a deeper question:

What makes someone leave the room in the first place?

That’s different for everyone.

- For some, it’s realizing a doctrinal contradiction.

- For others, it’s burnout—realizing that the love and peace they were promised is replaced with guilt, fear, and never being good enough.

- Some left during the COVID-19 doctrinal shift, when SCJ had to adjust its teaching to fit a reality it had not predicted—an example many cite as clear doctrinal change.

- For others, it’s the quiet, growing discomfort—the realization that the light they once followed now feels more like a spotlight trapping them, not guiding them.

And for some, it’s just the simple courage to open the door and see what’s outside.

Leaving the room doesn’t mean leaving God. It doesn’t mean rejecting the Bible. Sometimes, it’s the beginning of seeing things more clearly. The act of stepping out of an echo chamber is often the first real act of free will someone has made in a long time.

The analogy of the “strong scent” and “numbed eyes” is a powerful way to understand what happens when a person is deeply immersed in a high-control system. In SCJ, that system includes emotional pressure, constant repetition, and the belief that to doubt is to betray.

But truth doesn’t fear fresh air. And God is not afraid of your questions.

Sometimes, all it takes is a breath outside the room—and the courage to see it all again with new eyes.

One of the biggest things to think about when it comes to Shincheonji is this question:

Why is their truth so secret?

SCJ teaches that only they understand the Bible correctly. They believe that their leader, Lee Man-hee, is the one sent by Jesus—New John—and that the true meaning of the Bible was only revealed through him. This includes the belief that only SCJ knows how to be saved.

But when we look at the Bible and the way Jesus taught, this idea doesn’t line up.

Jesus didn’t teach in secret. In John 18:20, Jesus says, “I have spoken openly to the world… I said nothing in secret.” He taught in public places like synagogues, hillsides, and people’s homes. His miracles were seen by crowds. After His resurrection, over 500 people saw Him alive (1 Corinthians 15:6). That’s a lot of witnesses—not just one person’s testimony.

And in the Bible, truth is not meant to be hidden or held by one man alone. In Deuteronomy 19:15 and 2 Corinthians 13:1, it says that truth should be confirmed by two or three witnesses. Even the apostles didn’t just believe each other without question—Paul publicly corrected Peter in Galatians 2 when Peter was acting hypocritically. That shows even church leaders were held accountable.

Jesus also warned us: “If anyone says to you, ‘Look, here is the Messiah!’ or ‘There He is!’ do not believe it” (Matthew 24:23–24). That’s a strong warning. He knew that many would come later claiming to be sent by God. He told us to be careful.

If we’re to rely solely on God’s Word and let Him speak to our hearts, shouldn’t we also question whether any group, including SCJ, could be adding their own lens to the scriptures? After all, the Bible warns us to test every spirit in 1 John 4:1 to make sure that what we’re hearing is truly from God, not from a false prophet. But SCJ’s teaching doesn’t allow for that kind of open testing anymore.

How do you know it’s God’s voice and not an organization’s influence guiding your understanding? They claim to encourage it at the beginning—but once you’re inside, questioning is seen as rebellion or slander.

And history shows us a pattern: many people have claimed to receive private messages from God, without any public confirmation. For example:

- Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, said he received golden plates from an angel. But no one else could see them.

- Muhammad, the founder of Islam, said he received messages from Allah through the angel Gabriel, but again—he was the only one who experienced it.

- Sun Myung Moon, from the Unification Church, claimed he had divine revelations that only he understood.

In all these cases, the message depended on believing just one person’s word.

That’s what’s happening in SCJ, too. They say their message is “too difficult for most people to accept,” and compare it to Jesus saying, “You must eat my flesh and drink my blood” (John 6:53–56)—which many people found hard to accept. But here’s the difference: Jesus said that in public, in front of a crowd, and He didn’t stop people from walking away. His teaching was open, not hidden.

SCJ says they hide their identity to avoid “persecution” or “enemies.” But this raises a serious question: If what they teach is true, why hide?

Many other religious groups—even controversial ones—make their teachings public. Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and the Unification Church publish their doctrines online and welcome public discussion. But SCJ is much more secretive, especially during recruitment. Why?

They say it’s to “protect the sheep from the wolves”—but others say it’s a way to control the message and prevent questions before students are emotionally committed.

This also brings up the topic of free will. If someone is being guided step by step, slowly brought into something without knowing where it’s going, can we really say they made a free and informed choice? If the teaching is only revealed after loyalty is formed, it becomes hard to leave. That’s not freedom—that’s manipulation.

The Bible shows us that God doesn’t work through one person only. In 1 Kings 19:14–18, Elijah thought he was the only prophet left. But God told him there were 7,000 others who hadn’t bowed to Baal. That reminds us: God always has a remnant, and His truth doesn’t rely on one man.

And there’s something else to consider. SCJ says that Christian churches are Babylon, and that they’re full of false doctrine. But if that’s true—why are Christians the most persecuted group in the world today?

If Satan controls Babylon, why would he be attacking it so hard?

In Mark 3:24, Jesus says, “If a kingdom is divided against itself, that kingdom cannot stand.” So if Christians are being attacked, maybe it’s not because they’re false—but because they’re a real threat to darkness. That’s something worth thinking about.

Jesus said, “You are the light of the world” (Matthew 5:14). Light doesn’t hide. It shines where everyone can see it. That’s very different from secret Bible classes, hidden church names, or teachings that say “you’ll only understand after months of study.”

Real truth doesn’t need to be protected like a secret.

It’s meant to be shared—boldly, openly, and with love.

Membership, The “Fruit” of Recruitment

In Shincheonji (SCJ), salvation isn’t just about knowing God or believing in Jesus. It’s closely tied to completing their Bible study course, passing doctrinal tests, and joining a specific tribe within the church. Only then, they teach, can you be part of the 144,000 sealed—the group they believe is saved and eligible to enter heaven.

This is where the idea of “fruit” comes in.

When a student finishes the course and “passes over” (converts), they are considered the fruit of the SCJ member or tribe that invited them. Each tribe is given quotas, and members are told to keep producing fruit—that is, bringing in new people—to stay faithful and obedient to God’s will.

Recruiting others becomes a spiritual duty. Evangelism is no longer just sharing the good news—it’s a requirement tied directly to one’s own salvation. As they often say in SCJ, “The most precious work is saving a soul.” But in practice, that often means recruiting to meet goals, not necessarily helping someone walk with Jesus.

This raises an important question:

What happens to people who don’t—or can’t—go through this process?

There are many groups of people who, by SCJ’s standards, wouldn’t qualify:

- People with mental illness or intellectual disabilities who struggle to memorize doctrine or take written tests

- Elderly individuals who experience memory loss or can’t sit through long lessons

- Children under 18, who SCJ members are told not to evangelize

- People without reliable internet access or those with demanding jobs and family obligations

- Christians who are committed to other churches but love and follow Jesus sincerely

- People from other faiths or countries who will never hear about SCJ

Are all these people left out of God’s salvation plan?

If SCJ is correct, then salvation is no longer accessible to all—it’s only for the strong, available, and selected few. It becomes a performance-based reward, not a gift of grace. This idea directly contradicts the message of the Bible.

Let’s look at what Scripture says instead:

- Titus 2:11 — “For the grace of God has appeared that offers salvation to all people.”

- Romans 10:13 — “Everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.”

- 2 Peter 3:9 — “The Lord is patient… not wanting anyone to perish, but everyone to come to repentance.”

These verses don’t mention Bible study courses, test scores, or monthly fruit quotas. They speak about a God who invites all people, regardless of their background, schedule, age, or mental capacity.

This brings us to a historical parallel:

In the 1500s, the Catholic Church sold indulgences—documents that claimed to reduce punishment for sins. People were told they could pay money to help themselves or their loved ones get out of purgatory. Salvation was no longer about grace—it became a transaction.

This led to the Protestant Reformation, where Martin Luther reminded the Church that salvation is by grace through faith, not by human effort or payment. He pointed to Ephesians 2:8–9, which says:

“For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God—not by works, so that no one can boast.”

SCJ may not ask for money like indulgences, but they do place conditions that act like currency:

Attend the full course. Pass the doctrinal tests. Join a tribe. Evangelize to prove your worth. Don’t fall behind.

This conditional salvation feels more like a contract than a covenant. You sign it with effort and loyalty, not by receiving God’s grace freely through Christ.

But Jesus never made people work their way to Him.

He did the opposite.

- He touched lepers who were considered unclean (Luke 5:12–13)

- He ate with tax collectors and sinners (Mark 2:15–17)

- He defended a woman caught in adultery, when others wanted to kill her (John 8:1–11)

- He welcomed children, saying “the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these” (Matthew 19:14)

He never said, “Come to Me after you finish a nine-month class.”

He said:

“Come to Me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.” (Matthew 11:28)

That’s the Jesus of the Bible.

Not a gatekeeper, but a shepherd.

Not a taskmaster, but a healer.

Not a recruiter, but a redeemer.

So if SCJ teaches that you need to complete their system to be saved—what does that say about free will? If the only way to be saved is through their group, then salvation becomes limited to those who conform, not those who respond to God with an open heart.

And what about the fruits of the Spirit—like love, joy, peace, kindness, and gentleness (Galatians 5:22–23)? These fruits grow naturally when someone walks with Jesus. But SCJ has redefined “fruit” to mean people you recruit. That’s a major shift from what the Bible actually says.

Former members say the intense Bible study and supportive community drew them in. But over time, they felt pressure to perform, to bring in new students, and to tie their salvation to obedience and success, not to grace.

That’s why many left feeling burned out, confused, or afraid—unsure whether God would still accept them now that they had “failed” the system.

But the truth is:

Jesus already paid the price.

There’s nothing left for us to earn—only to receive.

If salvation is not accessible to all, it’s not the gospel of Jesus.

Step Back, Breathe, and Test Everything

Shincheonji’s Bible study feels deep for a reason. The lessons seem rich, the teachers sound confident, and the early love is overwhelming. But many former members have come to see that this wasn’t accidental—it was carefully designed. The kindness, support, and constant attention—what many call “love bombing”—was meant to build emotional trust before you gave spiritual consent.

The deeper you go, the harder it becomes to question what’s really happening.

It’s like being in a room filled with a strong scent. At first, it’s all you notice. But stay long enough, and your senses adjust. The smell doesn’t go away—you just stop noticing it. You become numb to what once stood out clearly.

That’s what happens when you’re immersed in a single system of thought for too long. The verses repeat. The answers come fast. You’re constantly reinforced with the same ideas, the same phrases, and the same explanations. Slowly, it becomes an echo chamber—a space where only one voice is heard, and all others are pushed out.

In that environment, your ability to ask hard questions—or even recognize another perspective—fades. You don’t notice the shift, because it feels normal. Safe. Biblical.

But here’s the thing: You’re still allowed to leave the room.

You can crack a window. Step outside. Breathe fresh air. And when you come back—if you do—you’ll see things you couldn’t before. That’s what real discernment looks like.

It’s not about rejecting everything you’ve learned. It’s about making space to compare the claims, test what you’ve been taught, and ask:

“Is this really what the Bible says—or just what I was told it says?”

That question matters—because groups like Shincheonji often weave their teachings so tightly into the Bible that it becomes hard to see where Scripture ends and their theology begins. It’s like watching a Bible-based TV show where the lines between truth and fiction blur. If you don’t know the original, the rewritten version becomes your truth.

What starts as a sincere search for truth can slowly become a filtered version of faith, shaped by a single organization’s lens. And if we’re not grounded in God’s Word, the Bible, it’s easy to accept a message that feels biblical—but isn’t.

That’s why biblical literacy is so important. Not just to learn, but to discern.

Because even Satan quoted Scripture. And even deception can wear the voice of sincerity.

The Bible says, “Test the spirits to see whether they are from God.” (1 John 4:1) Real truth doesn’t silence your questions. Real love doesn’t manipulate. And real freedom in Christ doesn’t lock the door behind you.

So if you’re in that room—pause.

Crack a window. Ask a question. Take a step.

And trust this: God isn’t afraid of your doubts.

He’s still outside—waiting with grace, truth, and a better view.

Additional References for more Exploration

Related Collections: additional articles and details connected to this main article (themes, studies, and terms), offering context, depth, and insights that continue to grow over time. New titles will be added, much like books placed on a shelf as the collection expands.

In the teachings of Jesus, parables serve as illuminating windows that make spiritual truths accessible through everyday imagery. These simple stories about farmers, seeds, banquets, and lost coins were designed to reveal rather than conceal—to bring clarity rather than confusion. Yet in the hands of Shincheonji Church of Jesus, these same parables have been transformed into an elaborate system of coded messages that allegedly require special interpretation to unlock salvation.

At the center of Shincheonji’s theological framework stands what they call the “fundamental parable”—the parable of the sower (or sowing the seed), which they claim is the essential key without which no other biblical teaching can be properly understood. According to their doctrine, this parable, along with the parable of the wheat and weeds, establishes a rigid interpretive system where specific images always carry fixed meanings: seed always represents doctrine, field always represents the heart or church, birds always represent spirits, and so on.

This article examines Shincheonji’s claims about these parables and tests them against Scripture in its proper context. We’ll explore how a teaching meant to illuminate has been transformed into what effectively functions as a “decoder ring”—a proprietary system of interpretation that places additional requirements between believers and salvation. By contrasting Shincheonji’s complex parable system with the straightforward gospel message that salvation comes through faith in Christ’s finished work on the cross, we can better understand the profound theological shift that occurs when parables become puzzles requiring specialized knowledge rather than windows revealing God’s grace. [Read More]

In the landscape of contemporary religious movements, few organizations approach biblical interpretation with the distinctive methodology employed by Shincheonji Church of Jesus. Founded in 1984 by Lee Man-hee in South Korea, Shincheonji presents itself not merely as another Christian denomination, but as the exclusive recipient of divine revelation—possessors of an “open word” that unlocks biblical mysteries supposedly sealed until our present age.

At the heart of Shincheonji’s appeal is its intensive Bible study program, which promises to reveal “hidden truths” that mainstream Christianity has allegedly overlooked or misinterpreted for centuries. According to Shincheonji, the Bible is not primarily a straightforward historical or theological text, but rather an elaborate coded message where parables, symbols, and prophecies point to specific end-time realities—particularly to Shincheonji’s own organization, teachings, and leader.

This article examines Shincheonji’s distinctive approach to biblical interpretation, exploring how they employ parables, typology, and systematic interpretation to support their core doctrines about the Promised Pastor (Lee Man-hee), the Promised Temple (Shincheonji Church itself), and the Promised Teaching (their revealed theology). We’ll analyze how Shincheonji transforms conventional biblical imagery into a comprehensive symbolic system where virtually every significant biblical narrative or prophecy is reinterpreted to validate their exclusive claims.

By understanding Shincheonji’s Bible study methodology, we gain insight not only into why this movement has experienced rapid growth—particularly among those already familiar with Christianity—but also into the profound theological implications of their interpretive framework. For Shincheonji, biblical interpretation is not merely an academic exercise but the very foundation of salvation itself, as they teach that understanding their revealed meanings is essential for eternal life. This radical claim deserves careful examination, both for those encountering Shincheonji’s teachings and for those seeking to understand contemporary religious movements more broadly. [Read More]

In today’s polarized media landscape, we’ve become accustomed to seeing how a single event can be transformed into radically different narratives depending on who’s telling the story. A protest might be portrayed as a righteous stand for justice by one outlet and as violent chaos by another. The same incident can sound entirely different across rival news sources, with key details carefully selected or omitted to support a preferred storyline. This phenomenon of media bias—where facts are filtered through ideological lenses—offers a powerful metaphor for understanding religious movements that make extraordinary claims about historical events.

This principle becomes especially critical when examining religious organizations where eternal salvation is said to depend on accepting a particular version of events. Shincheonji Church of Jesus presents a compelling case study in this regard. The entire theological foundation of this South Korean religious movement rests on what it claims is the “physical fulfillment of Revelation” that occurred in South Korea between 1966 and 1984. Members are taught that understanding and believing Lee Man-hee’s testimony about these events is literally required for salvation.

However, much like a biased news report, Shincheonji’s account of these historical events appears highly selective when compared with court testimonies and historical records. The organization presents its narrative with meticulous detail using journalistic methods, complete with photographs and dramatic video presentations as “evidence” of biblical prophecy unfolding in real time. Yet students are strongly discouraged from consulting outside sources, which are characterized as “spiritual poison” that could corrupt their understanding.

This article examines the factual basis of Shincheonji’s origin story by contrasting the organization’s claims with documented historical evidence. It explores the social and religious context of post-war South Korea that gave rise to numerous apocalyptic movements, traces the genealogy of Korean messianic cults that influenced Shincheonji’s theology, and investigates Lee Man-hee’s religious journey before founding his organization. By separating verifiable facts from theological interpretation, we can better understand how historical events in South Korea have been reframed as divine fulfillment of biblical prophecy. [Read More]

Picture yourself as a detective examining the same crime scene through different investigative approaches. One detective sees a straightforward case of corporate fraud – following the money trail, analyzing financial records, and identifying clear motives for organizational takeover. Another detective, trained in psychological profiling, sees the same evidence as a complex narrative of personal betrayal, wounded pride, and emotional manipulation. A third investigator, specializing in religious movements, interprets the identical facts as a classic pattern of spiritual authority transfer and prophetic succession. Same evidence, same timeline, same people – yet three completely different stories emerge.

This is precisely what happens when we examine the events that took place in South Korea between 1966 and 1984 at a small church called the Tabernacle Temple in Gwacheon. The same historical facts can be understood through multiple interpretive frameworks – each revealing what appears to be a completely different reality with vastly different meanings and implications.

What makes this case study particularly intriguing is how the application or removal of what we might call the “parable filter” dramatically changes our perception of events. When we view these occurrences through the lens of spiritual symbolism and prophetic fulfillment – seeing every person as a biblical figure, every conflict as spiritual warfare, and every outcome as divine intervention – we witness an epic drama of eternal significance. However, when we remove this parable filter and examine the same events through secular, historical, or sociological frameworks, an entirely different narrative emerges. The prophetic figures become ordinary people with human motivations, the spiritual battles transform into organizational politics, and the divine interventions reveal themselves as strategic human decisions.

The question becomes: Which lens reveals truth, and which creates compelling fiction? Are we witnessing the fulfillment of ancient prophecies, or are we observing how ordinary events can be mythologized through the application of religious interpretive frameworks?

Understanding Interpretive Frameworks

An interpretive framework is like a specialized lens through which we process and make sense of events. It’s the underlying system of beliefs, training, and worldview that determines how we assign meaning to what we observe. Just as a medical doctor, an artist, and an engineer would each notice different aspects of the same building – structural integrity, aesthetic beauty, or functional design – human beings naturally apply different interpretive frameworks to make sense of their experiences.

Consider how the same historical event can be understood through various lenses:

- Economic Framework: Focus on financial motivations, resource allocation, and market dynamics

- Psychological Framework: Emphasis on personal relationships, emotional conflicts, and individual motivations

- Sociological Framework: Analysis of group dynamics, social hierarchies, and cultural influences

- Legal Framework: Examination of rights, responsibilities, and procedural compliance

- Spiritual Framework: Interpretation through religious doctrine, prophetic fulfillment, and divine intervention

These frameworks are not merely academic exercises. They shape our understanding of reality itself, influencing our decisions, relationships, and life choices. When it comes to religious or spiritual matters, the stakes become even higher, as these interpretations often claim to reveal ultimate truth about existence, purpose, and eternal destiny.

Multiple Realities from the Same Events

What makes the Shincheonji story particularly compelling is how the same sequence of documented historical events can generate distinctly different realities depending on which interpretive lens is applied:

The Corporate Reality reveals a familiar business narrative of organizational restructuring, leadership transitions, and institutional reform. Through this lens, we see strategic planning, competitive positioning, and systematic takeover of a religious organization following predictable patterns of corporate merger and acquisition.

The Personal Reality focuses on individual relationships, emotional dynamics, and human psychology. This framework reveals a story of mentorship gone wrong, personal ambition, betrayal of trust, and the complex motivations that drive people to seek power and recognition within religious communities.

The Spiritual Reality transforms these identical events into a divine drama of biblical proportions. Through this framework, the same people become prophetic figures fulfilling ancient biblical prophecies, their conflicts represent the eternal battle between God and Satan, and their actions carry significance for all humanity’s spiritual destiny.

At the heart of Shincheonji Church’s prophetic claims lies a dramatic narrative of persecution, destruction, and divine vindication. According to their teachings, the Tabernacle Temple—portrayed as God’s true holy place in South Korea—was maliciously destroyed by a coalition of religious enemies led by Pastor Oh Pyeong-ho and Rev. Tak Myung-hwan. This event is presented as the fulfillment of biblical prophecy, particularly Revelation 11:1-2, where the holy place is trampled by gentiles.

However, when we examine the historical record beyond Shincheonji’s theological filter, a starkly different picture emerges. The collapse of the Tabernacle Temple was not the result of religious persecution but rather the consequence of financial mismanagement, criminal fraud, and urban development. What Shincheonji portrays as a cosmic battle between good and evil was, in reality, a mundane series of events involving bankruptcy, property sales, and attempts at rehabilitation by mainstream Christian leaders.

This article separates fact from fiction regarding the key figures and organizations in Shincheonji’s narrative. It examines the actual circumstances surrounding the Tabernacle Temple’s downfall, the true nature of the Stewardship Education Center (SEC), and the real motivations of figures like Pastor Oh Pyeong-ho and Rev. Tak Myung-hwan. By contrasting verifiable historical evidence with Shincheonji’s claims, we can understand how a routine property transaction and rehabilitation effort has been transformed into an apocalyptic drama that serves as the foundation for Lee Man-hee’s prophetic authority.

Understanding this historical context is crucial not only for evaluating Shincheonji’s theological claims but also for recognizing how religious movements can rewrite history to create compelling narratives that validate their leaders’ authority and insulate members from outside information. [Read More]

At the heart of Shincheonji Church of Jesus (SCJ) lies a theological framework fundamentally different from mainstream Christianity. While traditional Christian faith centers on Jesus Christ’s death and resurrection as the complete foundation for salvation, Shincheonji has constructed an alternative system where salvation hinges on a specific understanding of prophetic fulfillment—particularly regarding the Book of Revelation.

This distinctive emphasis is not merely an academic difference or theological curiosity. For SCJ members, recognizing and accepting their leader Lee Man-hee’s interpretation of Revelation’s “physical fulfillment” in South Korea becomes the narrow gate to eternal life itself. Without this recognition, salvation is considered impossible, effectively making Lee the gatekeeper of heaven.

This article examines why prophetic fulfillment holds such extraordinary importance within Shincheonji’s doctrine, how it fundamentally alters the Christian understanding of salvation, and the problematic implications of tying eternal life to the recognition of one man’s interpretations of current events. By exploring SCJ’s claims against biblical standards for prophetic validation and contextualizing them within Korea’s unique landscape of messianic movements, we uncover the concerning theological shifts that transform Christianity’s message of grace into a system where salvation depends not on Christ alone, but on correctly identifying Lee Man-hee’s role in God’s unfolding plan. [Read More]

Throughout Scripture, we encounter a God who remains steadfast in His commitment to humanity even when they turn away from Him. From Genesis to Revelation, the biblical narrative reveals a God of enduring faithfulness, unwavering love, and sovereign power. This portrait stands in stark contrast to the deity presented by Shincheonji (SCJ), whose teachings fundamentally redefine God’s nature, character, and relationship with humanity.

SCJ presents a troubling theological framework where God repeatedly abandons His people when they fail, initiating cycles of betrayal, destruction, and salvation that require new “promised pastors” for each era. According to their doctrine, God operates within an eight-step pattern He cannot escape, portraying Him not as the sovereign ruler of all creation, but as a deity locked in an evenly matched 6,000-year conflict with Satan.

This examination contrasts SCJ’s portrait of a struggling, abandoning deity with the biblical God who declares, “Never will I leave you; never will I forsake you” (Hebrews 13:5). It explores how SCJ diminishes Christ’s completed work on the cross, redefines the Holy Spirit’s role, and creates a works-based salvation system dependent on organizational loyalty rather than faith in Christ alone. By comparing SCJ’s teachings with Scripture’s clear testimony, we uncover the profound theological distortions at the heart of their movement and reaffirm the true nature of God’s unfailing love and sovereign power. [read more]

In an age where truth itself seems under siege, how do we distinguish between genuine spiritual discernment and sophisticated manipulation? This critical examination explores one of the most challenging aspects of modern religious deception: how groups like Shincheonji Church of Jesus use biblical language, parable interpretation, and claims of spiritual warfare to create closed systems of thought that resist examination.

Through the lens of a real-life story—two Christians living in the same building but experiencing completely different realities—we’ll uncover how the same spiritual concepts can be twisted to justify harmful behavior while appearing deeply religious. This isn’t just about one organization; it’s about understanding the psychological and spiritual mechanisms that make people vulnerable to manipulation disguised as righteousness.

Every generation faces the challenge of communicating invisible spiritual realities through tangible examples. Jesus used parables for this very purpose—to make abstract spiritual truths accessible through familiar, concrete illustrations. But what happens when this powerful communication tool is weaponized? When parables become not bridges to understanding, but walls that separate people from truth?

The story you’re about to read reveals how Shincheonji has developed a sophisticated parable-based system that appears biblically grounded while making their organization absolutely essential for salvation. More importantly, it demonstrates how anyone—regardless of intelligence or spiritual maturity—can fall prey to manipulation when pride, fear, and the desire for exclusive truth converge.

We live in an era of competing narratives, where the same events can be interpreted in radically different ways depending on one’s framework. This phenomenon extends far beyond religion into politics, media, and social discourse. Understanding how spiritual manipulation works provides crucial insights into recognizing deception in all its forms.

This examination is not an attack on faith, but a defense of it. By learning to distinguish between genuine biblical Christianity and its counterfeits, we protect both ourselves and others from systems that use God’s name to advance human agendas. The stakes couldn’t be higher—not just for individual lives, but for the integrity of the Christian witness in a watching world. [Read More]

What Makes Shincheonji’s Bible Study So Compelling?

Imagine walking into a friendly Bible study where enthusiastic instructors promise to unlock the “true meaning” of Scripture—meanings that have been hidden for 2,000 years. They offer systematic teaching, clear answers to difficult questions, and a sense of belonging to an elite group that finally “gets it.” For many sincere Christians seeking deeper biblical understanding, this sounds like exactly what they’ve been looking for.

This is the appeal of Shincheonji’s Bible study program. It’s not random or chaotic—it’s a carefully designed, sophisticated curriculum that systematically builds over 6-9 months, progressively revealing doctrines that would seem shocking if presented on day one. Students don’t realize they’re being led through a strategic indoctrination process until they’re already deeply invested.

What This Series Offers

This 30-chapter series breaks down Shincheonji’s entire Bible study framework—from their Introductory Parables course to their Advanced Revelation teachings—examining how they construct their core doctrine of Betrayal, Destruction, and Salvation (BDS). We’ll investigate their claims about:

- The Promised Pastor (Lee Man-hee as “the one who overcomes”)

- The Promised Teaching (the revealed word of Revelation)

- The Promised Kingdom (Shincheonji as “New Spiritual Israel”)

Our Approach: Multiple Lenses for Comprehensive Understanding

Like detectives examining evidence from every angle, we’ll use multiple investigative frameworks:

- Biblical Analysis: Testing Shincheonji’s interpretations against Scripture in context

- Historical Lens: Examining the actual events at the Tabernacle Temple (1966-1984) without the “parable filter”

- Psychological Perspective: Understanding the manipulation techniques and thought reform processes

- Storytelling & Analogies: Making complex doctrines understandable through relatable examples

- Comparative Study: Seeing how the same events look dramatically different depending on which interpretive lens is applied

The Bible Calls Us to Test Everything

Scripture commands us: “Dear friends, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God, because many false prophets have gone out into the world” (1 John 4:1). The Bereans were commended because “they received the message with great eagerness and examined the Scriptures every day to see if what Paul said was true” (Acts 17:11).

Let’s Discern Together

This series provides you with comprehensive reports for your own investigation and research. We encourage you to:

- Cross-examine every claim against Scripture

- Conduct independent research rather than accepting any teaching at face value

- Think critically about the interpretive frameworks being used

- Verify historical claims and biblical interpretations

- Ask questions that demand clear, biblical answers

Whether you’re currently involved with Shincheonji, have loved ones in the organization, are a pastor concerned about your congregation, or simply want to understand this movement, this series equips you with the knowledge and tools to discern truth from deception.

We’re not asking you to simply believe our analysis—we’re inviting you to examine the evidence yourself. Like a courtroom presenting a case, we’ll lay out the facts, show you the patterns, test the claims against Scripture, and let you reach your own verdict.

The stakes are eternal. The call is clear: Test everything. Hold fast to what is good.

Let’s begin the investigation.