Imagine trying to explain the internet to someone from the first century. Picture yourself describing smartphones, airplanes, nuclear weapons, or even something as basic as electricity to a person whose fastest communication traveled at the speed of a horse, whose brightest light came from oil lamps, and whose understanding of the world was bounded by the horizon they could see. The concepts that seem obvious to us would be utterly foreign to them, not because they lacked intelligence, but because they lacked the cultural framework to understand these realities.

Now flip that scenario. When we read the Book of Revelation today, we may be in a similar position to that first-century person trying to understand modern technology. The difference is that we are modern people trying to understand an ancient text written in a cultural, political, and economic context that is largely foreign to us. The symbols, numbers, and imagery that would have been immediately recognizable to a first-century Christian, like an inside joke shared among friends, can leave us scratching our heads or, worse, confidently misinterpreting meanings that were never intended.

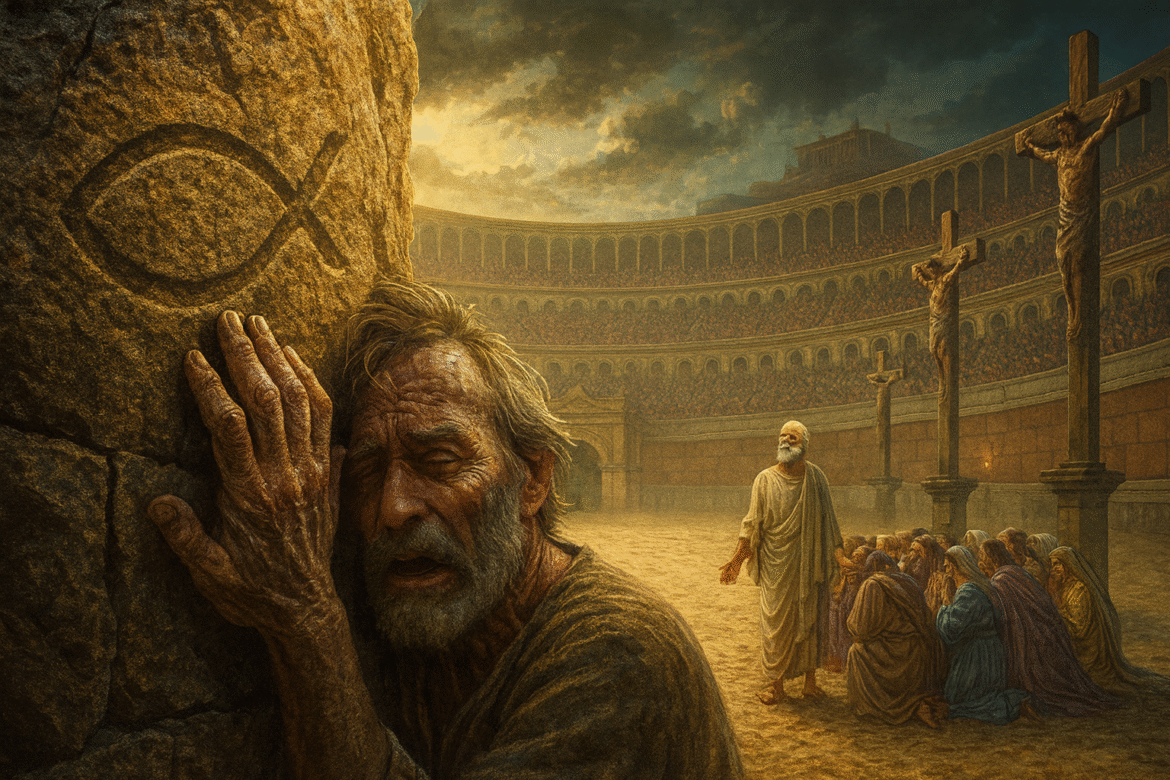

The first-century world was a powder keg of societal unrest, political oppression, and economic manipulation. Christians lived under the constant threat of persecution from an empire that demanded not just political loyalty but religious worship. They navigated complex trade guild systems where economic survival often meant compromising their faith. They spoke in coded language out of necessity, not mystery. When John wrote Revelation, he was not creating an elaborate puzzle for future generations to solve. He was speaking directly to people whose daily reality included imperial propaganda, emperor worship, economic boycotts, and the very real possibility of martyrdom.

Today, we have the luxury of academic debate about whether Revelation should be interpreted literally or figuratively, whether it describes past events or future prophecies, and whether the numbers are mathematical or symbolic. We publish countless books with conflicting interpretations, create elaborate charts mapping out end-times scenarios, and sometimes become so focused on predicting when Jesus will return that we forget to examine whether we are ready to meet Him today.

What stands out as we dive into this study is that the first-century Christians who first received John’s letter were not primarily concerned with decoding a timeline for the distant future. They were asking more immediate and personal questions: “How do I live faithfully under an oppressive regime? How do I feed my family when participating in the economy requires compromising my faith? How do I find hope when my friends are being thrown to lions? How do I make sense of suffering when I am supposed to be following the Prince of Peace?”

Perhaps this is where our focus should remain, even as we explore the rich historical and cultural context of Revelation. The most important question is not “When will Jesus return?” but “Am I ready to meet Him today?” It is not “How will the world end?” but “How is my heart toward God right now?” It is not “What do these symbols predict about the future?” but “What is God saying to my soul through His Word today?”

As we examine how first-century Christians might have understood Revelation’s imagery, its numbers, symbols, and coded language, we do so not to claim the final word on interpretation, but to enrich our understanding and deepen our discernment. There are many faithful scholars who would disagree with the interpretations presented here, and that is not only acceptable but healthy. The goal is not uniformity of interpretation but unity in our love for Christ and our commitment to live faithfully in whatever circumstances we face.

So as you read this exploration of Revelation through first-century eyes, hold it lightly. Test everything against Scripture. Seek the Holy Spirit’s wisdom. Remember that historical context, while valuable, is a tool for understanding, not a replacement for personal relationship with God. And ultimately, let whatever insights emerge drive you not to prophetic speculation but to heart examination: Are you walking closely with Jesus? Have you surrendered completely to Him as Lord and Savior? If He returned today, would you be ready to meet Him without shame?

The Book of Revelation, whatever else it may be, is fundamentally a book about Jesus Christ, His victory, His glory, His love for His people, and His ultimate triumph over every force that opposes Him. May our study lead us not just to better understanding, but to deeper worship, greater faithfulness, and more complete surrender to the One who holds the keys of death and Hades and who promises to make all things new.

Read with discernment. Study with humility. And above all, seek the Lord with your whole heart, for He rewards those who earnestly seek Him.

“But about that day or hour no one knows, not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father. Be on guard! Be alert! You do not know when that time will come… Therefore keep watch because you do not know when the owner of the house will come back… If he comes suddenly, do not let him find you sleeping. What I say to you, I say to everyone: ‘Watch!'” – Mark 13:32-37

The Book of Revelation might sound mysterious to us now, but for the first Christians who first heard it, it was a message that spoke directly into their lives. It was not some distant code about events thousands of years away. It was a lifeline of hope, a steadying hand in the middle of a storm.

It was late in the first century, and the Roman Empire cast a long shadow over Christian believers. Emperor Domitian, who ruled from AD 81 to 96, demanded to be hailed as “Lord and God” and did not tolerate dissent. Christians who refused to worship the emperor as god were seen as traitors. Loyalty to Jesus instead of Caesar could mean losing your livelihood, your freedom, or your life. Domitian promoted the cult of emperor-worship throughout the empire, insisting on divine honors for himself, and anyone who refused to join in calling Caesar “Lord” risked being accused of treason. (read more)

Many had not forgotten the earlier horrors under Nero, (read more) when believers were burned alive as human torches or thrown to wild animals while crowds cheered. Domitian’s persecution was not as constant or empire-wide, but it still reached deep into the provinces, especially in Asia Minor, where John’s seven churches were located. In cities like Smyrna, Pergamum, and Ephesus, Christians faced hostility from pagan neighbors and the suspicion of Roman officials. Refusing to take part in sacrifices to pagan gods or the emperor meant losing your place in trade guilds, which could quickly lead to poverty. (read more) Some, like Antipas of Pergamum, were killed for their faith (Revelation 2:13). To the church in Smyrna, John passed on Jesus’ own words: “Do not fear what you are about to suffer… Be faithful unto death, and I will give you the crown of life” (Revelation 2:10). These were not poetic phrases for a far-off future. They were urgent, personal, and spoken into the lives of people who risked everything to remain faithful.

Apostle John was one of those believers who paid the price. He was banished by Domitian to the rocky Aegean island of Patmos “on account of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus” (Revelation 1:9). Patmos was not an escape or a quiet retreat. It was a prison colony where Rome sent those it wanted silenced. John was far from home, cut off from his brothers and sisters in the faith, yet still in touch through passing ships and exchanged messages. (read more)

It was there, near the end of Domitian’s reign, that John received a breathtaking vision. He saw Jesus “standing among seven golden lampstands,” shining like the sun and holding seven stars (Revelation 1:12–20). The lampstands were the seven churches of Asia Minor: Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea. The risen Jesus told him, “Write in a book what you see and send it to the seven churches.” That book was called Revelation, “Apokalypsis,” an unveiling.

The empire that ruled over them was not gentle. Christians had seen believers hunted down, dragged into courts, stripped of property, imprisoned, enslaved, or executed. The shadow of Rome’s power was everywhere, and its message was clear: no one could resist the empire and live.

This is why the way John wrote Revelation mattered so much. Its vivid visions of beasts, thrones, angels, plagues, the fall of Babylon, and the conquering Lamb were not strange or mysterious to his first readers. The imagery, the symbolic numbers like 666, and the references to oppressive cities and rulers were all drawn from language and symbols they already knew from Scripture and from life under Roman rule. To them, it was like reading a political cartoon. The message was hidden in symbolic scenes that made perfect sense to those who shared the same experiences and history, yet could pass unnoticed or seem harmless to Roman soldiers or officials. They would see a beast with seven heads and understand it as the line of emperors, recall the cruelty of Nero, and know that Babylon was a thinly veiled name for Rome.

For the faithful, this was not an intellectual puzzle but a shared language of hope and defiance. It was as if John was looking each believer in the eye and saying, “We know who they are. We know what they do. But we also know who wins.” (read more)

In those days, Rome was not only a power with armies and coins, it was a power that demanded the soul. The emperor’s face was on the money. His name was in the prayers. His image stood tall in the temples. The Roman imperial cult compelled worship of the emperor as god, pressing the claim that he was divine and worthy of sacrifice and praise. This was not simply loyalty to a ruler, it was the surrender of worship that belonged only to the Lord.

But Revelation painted a different picture. Rome was no golden savior, it was “the beast,” a servant of something darker, tied to the cosmic forces of evil. The book told of another King, Jesus, who would not be toppled, who would not grow old, whose victory was certain. His triumph was not carved in marble or carried on a standard, it was written in heaven.

For those who followed Him, this changed everything. Suffering was not a mark of failure, it was a badge of loyalty. When Rome crushed them, mocked them, or stripped them of home and life, Revelation told them this was not the end. This was the battlefield, and their wounds were proof they were fighting on the right side. In God’s eyes, they were already victors. (read more)

This stripped the emperor’s throne of its divine mask. If his empire’s power came from the beast, then his claim to be a god was hollow. His marble temples were no more sacred than the dust on the streets. The grand speeches, the parades, the festivals were props in a story meant to hide the truth.

And so, Revelation’s coded visions were more than strange pictures. They were sharp, dangerous, and full of meaning, a holy satire aimed at the empire’s pride. They reminded the churches that no matter how unstoppable Rome appeared, its power was temporary. The Lamb had already won.

When Caesar Became God: The Roman Story Behind Revelation

Picture this: The year is 33 AD. Jesus has just ascended to heaven, leaving behind a small group of followers in Jerusalem. They have no idea that over the next 65 years, they’ll face an empire that wants not just their taxes and obedience, but their very souls.

The Seeds of Conflict

When Jesus left, Rome seemed like just another occupying force in Jewish lands: annoying, yes, but manageable. The empire collected taxes, kept the peace, and mostly let people worship their own gods. But something was changing in Rome itself, something dark and demanding.

You see, Rome had a problem. How do you hold together an empire stretching from Britain to Africa, from Spain to Syria? How do you unite people who speak different languages, worship different gods, and have different customs? The answer Rome found was simple: make the emperor a god.

It started slowly. Julius Caesar was declared divine after his death. Augustus, the first true emperor, was careful; he allowed himself to be worshiped as a god in the eastern provinces but played it down in Rome itself. But each emperor pushed the boundary a little further.

The Emperor Parade: From Tolerance to Terror

Let me walk you through the emperors who ruled from Jesus’ ascension to John’s exile:

Tiberius (14-37 AD) ruled when Jesus died and rose again. He was a gloomy, suspicious man who mostly left Christians alone because they were too small to notice.

Caligula (37-41 AD) was the first real warning sign. This young emperor went mad with power, demanding to be worshiped as a living god. He even tried to put his statue in the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem! Only his assassination prevented a massive Jewish revolt. Christians watched in horror: if this was how Rome treated the Jewish God, what would happen to followers of Jesus?

Claudius (41-54 AD) brought a brief calm. But he expelled Jews from Rome because of riots “about someone named Chrestus” (probably disputes between Jews and Jewish Christians about Jesus).

Nero (54-68 AD)… ah, Nero. Here’s where the story turns dark. In 64 AD, a great fire destroyed much of Rome. People whispered that Nero himself started it to clear land for his palace. To deflect blame, Nero pointed at the Christians.

The Roman historian Tacitus tells us what happened next: Christians were arrested, tortured, and killed in the most creative and cruel ways. Some were sewn into animal skins and torn apart by dogs. Others were crucified. And some (this still makes me shudder) were covered in pitch and burned alive as human torches to light Nero’s garden parties.

This was new. This wasn’t local hostility or religious disagreement. This was the empire itself turning Christians into entertainment.

After Nero came a year of chaos: 69 AD saw four emperors (Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and finally Vespasian) fight for power. Then:

Vespasian (69-79 AD) and Titus (79-81 AD) were too busy crushing the Jewish revolt and destroying Jerusalem’s temple (70 AD) to focus much on Christians.

But then came Domitian (81-96 AD), and with him, a new level of emperor worship.

The Babylon Connection: A Story Repeating Itself

Now, here’s where it gets interesting. Any Jewish Christian hearing about these demands for emperor worship would have felt a chill of recognition. They’d heard this story before, in the Book of Daniel.

Remember Nebuchadnezzar, the king of Babylon? He built a golden statue and commanded everyone to bow down and worship it. When Daniel’s three friends (Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego) refused, they were thrown into a fiery furnace (Daniel 3:1-30). Later, when Daniel refused to pray to King Darius instead of God, he was thrown to the lions (Daniel 6:1-28).

The parallels were impossible to miss:

- Ancient Babylon demanded worship of the king’s image / Rome demanded worship of the emperor

- Refusal meant the furnace / Refusal meant being burned as human torches

- Daniel faced lions / Christians were thrown to wild beasts in the arena

- Babylon destroyed the first temple / Rome destroyed the second temple

- Jews were exiled in Babylon / Christians were outcasts in the Roman Empire

It was as if history was repeating itself, but on a much larger scale. Where Babylon was one kingdom, Rome ruled the known world. Where Nebuchadnezzar was one king, Rome was a succession of emperors, each one potentially worse than the last.

The Ghost of Nero: When Numbers Tell a Story

Here’s something that would make your skin crawl if you were a first-century Christian: people genuinely believed Nero would come back from the dead.

This wasn’t just a crazy conspiracy theory. After Nero committed suicide in 68 AD, rumors spread immediately that he had escaped to the East. Over the next twenty years, at least three different imposters claimed to be Nero and gathered followings. The last known false Nero appeared as late as 88 AD, during Domitian’s reign!

Roman historians recorded this fear. Tacitus mentions it. Suetonius writes about it. Even pagan writers like Dio Chrysostom reference the belief that Nero would return. The Sibylline Oracles, a collection of prophecies popular in the ancient world, spoke of Nero fleeing beyond the Euphrates River and returning with armies.

This “Nero Redivivus” (Nero Revived) legend was so widespread that when John wrote about a beast whose “mortal wound was healed” (Revelation 13:3), every reader would have thought of Nero. The beast that “was, and is not, and is about to rise” (Revelation 17:8) perfectly captured their fear of a returning Nero. (read more)

But here’s where it gets mathematically fascinating and deeply symbolic. When John wrote “This calls for wisdom: let the one who has understanding calculate the number of the beast, for it is the number of a man, and his number is 666” (Revelation 13:18), he was inviting his readers to unpack multiple layers of meaning.

The Solomon Connection: When Wealth Becomes a Beast

Any Jewish Christian would have immediately remembered where they’d seen this number before. In 1 Kings 10:14 and 2 Chronicles 9:13, we read: “The weight of gold that came to Solomon in one year was 666 talents of gold.”

Think about what Solomon represented by the end of his reign. He started as the wise king who built God’s temple, but he ended as a cautionary tale. His wealth led to excess. His 700 wives and 300 concubines turned his heart away from God (1 Kings 11:3). He built high places for foreign gods (1 Kings 11:7-8). He taxed his people heavily and used forced labor (1 Kings 12:4). The very wealth symbolized by those 666 talents of gold became his downfall.

Now look at Rome through first-century Christian eyes. Like Solomon, Rome had incredible wealth and wisdom. Like Solomon, Rome built magnificent temples (but to false gods and emperors). Like Solomon, Rome’s wealth came through heavy taxation and forced labor. Like Solomon, Rome had been seduced away from any acknowledgment of the true God.

The number 666 thus became a perfect symbol: the number of human power and wealth that rebels against God. It was the number of a system that starts with promise but ends in oppression and idolatry. (Read more → The Stranglehold of Trade Guilds: Economic Warfare Against Faith, The Mark of the Beast)

The Nero Calculation: When Letters Become Numbers

But John added another layer. In both Hebrew and Greek, letters also served as numbers. This practice, called gematria, was common in the ancient world. And when you write “Nero Caesar” in Hebrew letters (נרון קסר), something remarkable happens:

- Nun (נ) = 50

- Resh (ר) = 200

- Vav (ו) = 6

- Nun (נ) = 50

- Qoph (ק) = 100

- Samech (ס) = 60

- Resh (ר) = 200

Total = 666

This wasn’t coincidence. John specifically said to “calculate” the number, using a word that implied mathematical computation.

Even more convincing: some ancient manuscripts have 616 instead of 666. Why? When you spell “Nero Caesar” in Latin rather than Hebrew, dropping the final “n” (Nero Caesar vs. Neron Caesar), you get 616. This variation actually proves the Nero connection; scribes familiar with different spellings of Nero’s name adjusted the number accordingly.

The Imperfect Number: Falling Short of God’s Perfection

But there’s yet another layer. In biblical numerology, seven represents perfection and completeness (God created the world in seven days, Revelation has seven churches, seven seals, seven trumpets). Six, being one short of seven, represents imperfection, incompleteness, and human failure.

So 666 is triple imperfection. It’s emphasis by repetition, like saying “utterly failed” or “completely incomplete.” It’s humanity trying to reach divine status but always falling short. The Roman emperors declared themselves gods, but they were just sixes pretending to be sevens. They were human, all too human, despite their claims to divinity.

How First-Century Christians Would Have Heard This

Imagine being a first-century Christian hearing Revelation read aloud in your house church. When you heard “666,” your mind would have raced through all these connections:

- “That’s Solomon’s gold! The wealth that corrupted the wisest king!”

- “That’s Nero’s name! The emperor who burned us alive!”

- “That’s the number of human failure, repeated three times!”

All these meanings would have layered on top of each other, creating a rich, multi-dimensional symbol. The beast wasn’t just Nero, though Nero embodied it. The beast wasn’t just wealth and power, though it used both. The beast was the whole system of human rebellion against God, whether in Solomon’s Jerusalem or Nero’s Rome.

To first-century Christians, this number wasn’t a mysterious code for a future antichrist. It was a profound commentary on the empire under which they lived: wealthy like Solomon but corrupt like him too, cruel like Nero and possibly returning like him, and ultimately just another human system pretending to be divine but falling short, short, short of God’s perfect seven.

This is why John called for “wisdom” and “understanding” to calculate the number. It wasn’t just about doing math; it was about seeing through the empire’s propaganda to its true nature. It was about recognizing that whether in Solomon’s gold or Nero’s cruelty, human power divorced from God always becomes beastly.

Why Rome Became “Babylon the Great”

John didn’t call Rome by its name. Instead, he used a code word that every Jewish reader would understand: Babylon. But why Babylon? Let me count the ways:

Historical Parallels:

Just as Babylon destroyed Solomon’s Temple in 586 BC (2 Kings 25:8-9), Rome destroyed the Second Temple in 70 AD. Just as Babylon carried Jews into exile (2 Kings 25:11), Rome scattered Jews and Christians across the empire. Just as Babylon was the superpower of its day, Rome dominated the known world.

Moral Parallels:

The prophet Isaiah had called ancient Babylon a prostitute (Isaiah 47:1-15). Jeremiah described Babylon as a golden cup making the nations drunk (Jeremiah 51:7). John picked up this exact imagery: “Babylon the great, mother of prostitutes… with whom the kings of the earth have committed sexual immorality, and with the wine of whose sexual immorality the dwellers on earth have become drunk” (Revelation 17:1-2, 5).

The Seven Hills Mystery:

Now here’s where geography meets prophecy. John describes seeing “a woman sitting on a scarlet beast that was full of blasphemous names, and it had seven heads and ten horns” (Revelation 17:3). Then he explains: “The seven heads are seven mountains on which the woman is seated” (Revelation 17:9).

Every first-century reader knew Rome as the “City of Seven Hills.” These hills were:

- Palatine (where the emperors lived)

- Capitoline (the religious center)

- Aventine

- Esquiline

- Caelian

- Quirinal

- Viminal

Roman coins, Roman poetry, and Roman propaganda all celebrated the seven hills. Calling Rome the city on seven mountains was like saying “the Big Apple” for New York today; everyone knew what you meant.

But John adds another layer: “They are also seven kings, five of whom have fallen, one is, the other has not yet come” (Revelation 17:10). Here’s where it gets interesting. If John was writing during Domitian’s reign, the five fallen emperors could be:

- Augustus (fallen)

- Tiberius (fallen)

- Caligula (fallen)

- Claudius (fallen)

- Nero (fallen)

- Vespasian (if “one is” refers to him) or Domitian (if counting differently)

- The one “not yet come”

Different scholars count differently, sometimes skipping the three emperors who ruled briefly in 69 AD, sometimes starting with Julius Caesar. But the point wasn’t mathematical precision; it was showing that Rome’s imperial power, like Babylon’s, was numbered and would fall.

Why Rome Hated Christians

But why did Rome turn against Christians specifically? After all, the empire was full of different religions. Here’s what made Christians different (and dangerous) in Roman eyes:

- They were exclusive. Other religions could add the emperor to their list of gods. Christians said there was only one Lord, and it wasn’t Caesar.

- They were growing. What started as a handful of people in Jerusalem was spreading across the empire like wildfire. Slaves, soldiers, merchants, even some nobles were converting.

- They were connected. Christians formed tight-knit communities that crossed social boundaries. Slaves and masters called each other “brother.” This threatened the social order Rome depended on.

- They were mysterious. Christians met in private, shared a meal they called the “body and blood” of their Lord, and called each other “brother and sister” even when not related. Rumors spread that they were cannibals and practiced incest.

- They wouldn’t participate. Much of civic life involved some form of emperor worship or sacrifice to Roman gods. Christians couldn’t join trade guilds, attend certain festivals, or participate in civic ceremonies. They seemed anti-social and unpatriotic.

Most dangerously, Christians proclaimed that Jesus, not Caesar, was Lord. In an empire where “Caesar is Lord” was both a political statement and a religious creed, saying “Jesus is Lord” was treason.

The Political Climate: An Empire on Edge

By the time John was exiled to Patmos around 95 AD, Rome was paranoid. Domitian saw conspiracies everywhere. He demanded to be addressed as “Lord and God” (Dominus et Deus). He revived the imperial cult with new intensity, making emperor worship a test of loyalty.

The empire was also struggling with its own success. It had grown so large it was hard to control. Barbarian tribes pressed on the borders. The economy was strained. The old Roman values were crumbling under the weight of wealth and power. Domitian, like many dictators, used fear and religious fervor to maintain control.

In this climate, Christians stood out like sore thumbs. They wouldn’t burn incense to the emperor’s image. They wouldn’t swear by his divine spirit. They met secretly and spoke of another kingdom. To Roman eyes, they were a cancer that needed to be cut out.

The Stage Is Set

So by the time John received his vision on Patmos, Christians had experienced:

- The mad emperor worship of Caligula

- The brutal entertainment killings under Nero

- The destruction of Jerusalem, showing Rome’s willingness to crush religious resistance

- The increasing pressure under Domitian to worship the emperor or die

They were living through their own Babylonian exile, but worse. At least Daniel and his friends faced one king at a time. Christians faced an entire system, an empire that regenerated with each new emperor, sometimes worse than before.

And just like the Jewish exiles in Babylon turned to apocalyptic visions and prophecies for hope, so John’s readers would have immediately understood his imagery. The beast with seven heads? Of course: the seven hills of Rome and the line of emperors. Babylon the Great? Obviously Rome, the new destroyer of God’s people. The demand for the mark of the beast? They lived it every day when asked to acknowledge Caesar as divine.

The Book of Revelation wasn’t a mysterious code about the distant future. It was a survival manual for the present, written in the language of Daniel and Ezekiel, for people living through their own Babylon experience. But where Daniel saw four beasts representing four kingdoms, John saw a beast that seemed to resurrect itself with each new emperor: an undying enemy that only the true Lord could defeat.

This was the world that first heard Revelation: an empire that demanded worship, believers who refused to bow, and the echoing memory of ancient Babylon reminding them that God’s people had faced this before… and survived.

The Living Word: How Scripture Shaped First-Century Faith and Revelation’s Message

When Scripture Was a Sound, Not a Page

Imagine you’re a first-century Christian in Ephesus. You can’t run to the bookstore and buy a Bible. You probably can’t read anyway – maybe only 10% of the population was literate. So how do you know the scriptures that Revelation constantly references?

The answer is beautiful: scripture lived in the community’s memory and voices, not on pages.

Every Sabbath in the synagogue (where Jewish Christians still worshiped before the final break), you’d hear the Torah chanted in Hebrew, followed by translations and explanations in your everyday language. The readings followed a set cycle – after three years, you’d have heard the entire Torah. The Prophets and Writings were read too, especially on feast days. A devoted Jew would hear Deuteronomy recited completely during Sukkot, the entire book of Esther at Purim, and Isaiah 53 on Yom Kippur.

By the time someone reached adulthood, they’d have heard Genesis hundreds of times. They knew the Exodus story by heart. Daniel’s visions of beasts and kingdoms? They’d heard them dramatized every time foreign oppression intensified. The Psalms weren’t just read – they were sung, embedding themselves in memory through melody.

This oral culture created something remarkable: a shared scriptural vocabulary that didn’t depend on personal copies or literacy. When John wrote “a Lamb standing as though it had been slain” (Revelation 5:6), every hearer immediately thought of Isaiah 53: “He was led like a lamb to the slaughter.” When he described a beast rising from the sea, they instantly recalled Daniel 7. These weren’t obscure references requiring footnotes – they were common knowledge, as familiar as nursery rhymes are to us.

Jesus: The Master of Scriptural Echoes

But here’s what changed everything: Jesus himself showed them how to read scripture as all pointing to him. This wasn’t arrogance – it was revelation.

From the very beginning of his ministry, Jesus demonstrated that scripture wasn’t just ancient history but living prophecy. In the Nazareth synagogue, he read Isaiah 61: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor.” Then he sat down and declared, “Today this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing” (Luke 4:18-21).

The crowd’s reaction? They tried to throw him off a cliff. Why? Because he was claiming that their memorized, recited, cherished scriptures were actually about him, happening right now, in their village synagogue.

Throughout his ministry, Jesus kept doing this. When John the Baptist sent messengers asking if Jesus was “the one who is to come,” Jesus answered by echoing Isaiah: “The blind receive sight, the lame walk, those who have leprosy are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised” (Matthew 11:5). He didn’t say “Yes, I’m the Messiah.” He let scripture say it for him.

This pattern intensified during his passion. In the garden, when the soldiers came to arrest him, Jesus said, “But how then would the Scriptures be fulfilled that say it must happen in this way?” (Matthew 26:54). He wasn’t fatalistic – he was showing that even his arrest was part of the story scripture had been telling all along.

On the cross, Jesus didn’t give a personal statement. Instead, he recited Psalm 22: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46). Every Jew knew this psalm by heart. They knew it began in despair but ended in triumph: “All the ends of the earth will remember and turn to the Lord” (Psalm 22:27). By starting this psalm, Jesus was telling them: “This looks like defeat, but remember how the song ends.”

His final words came from Psalm 31: “Into your hands I commit my spirit” (Luke 23:46). Even in death, Jesus was teaching them to see his story through scripture’s lens.

The Apostolic Echo Chamber

After the resurrection, Jesus’ followers finally understood. On the road to Emmaus, the risen Christ explained “what was said in all the Scriptures concerning himself” (Luke 24:27). Their hearts burned within them as familiar passages suddenly blazed with new meaning.

This became the apostolic method. When Peter preached at Pentecost, he didn’t give his personal testimony. He quoted Joel, David, and the Psalms, showing how scripture pointed to what just happened (Acts 2). When Philip met the Ethiopian eunuch reading Isaiah 53, he “began with that very passage of Scripture and told him the good news about Jesus” (Acts 8:35).

Paul’s letters are saturated with Old Testament references – scholars count over 200 direct quotes and thousands of allusions. He assumed his readers, even Gentile converts, would recognize these references. Why? Because the first thing new Christians learned was how their story connected to Israel’s story.

This created an interpretive tradition: scripture wasn’t a dead letter but a living witness to Christ. Every story, every prophecy, every psalm could suddenly reveal Jesus. The Passover lamb? That’s Jesus. The rock that gave water in the wilderness? That’s Jesus. The temple? That’s Jesus’ body. The bronze serpent lifted up for healing? That’s Jesus on the cross.

The Circulation of Sacred Understanding

But how did this understanding spread across the empire? Through a remarkable network of letters and traveling teachers.

The apostolic letters weren’t private correspondence – they were public documents meant to be read aloud in assemblies. Paul explicitly commands: “After this letter has been read to you, see that it is also read in the church of the Laodiceans” (Colossians 4:16). These letters circulated from church to church, creating a shared interpretive framework.

Traveling teachers and prophets carried oral tradition between communities. When they arrived, they’d be tested against the scriptures and the received tradition. John warns about this in his letters: “Dear friends, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God” (1 John 4:1). The test? Whether their teaching aligned with scripture and the apostolic witness about Jesus.

This system created accountability. If someone in Corinth started teaching that Jesus wasn’t really human, the church in Ephesus could send a letter saying, “That contradicts what John taught us.” If someone in Rome claimed special revelation, it could be checked against Paul’s letters circulating from Jerusalem.

From Suffering Servant to Conquering King

This brings us to Revelation’s unique contribution. The Gospels and most apostolic preaching focused on Jesus as the Suffering Servant of Isaiah 53 – rejected, wounded, dying for others. This was crucial for understanding why the Messiah had to die.

But Revelation reveals the rest of the story. The same Jesus who came as a servant is returning as King. The Lamb who was slain is also the Lion of Judah. The one who washed feet will tread the winepress of God’s wrath. The teacher who turned the other cheek will strike down nations with the sword of his mouth.

This isn’t contradiction – it’s completion. The Old Testament prophets saw both images but couldn’t reconcile them. Isaiah saw both the Suffering Servant (Isaiah 53) and the Conquering King (Isaiah 63). Zechariah described both the humble king on a donkey (Zechariah 9:9) and the Lord standing on the Mount of Olives to fight for Jerusalem (Zechariah 14:4).

First-century Christians lived between these two portraits. They’d experienced Jesus as servant but awaited him as king. Revelation shows how both are true, how suffering leads to glory, how the cross becomes the throne.

The Scripture-Soaked Vision

When John received his vision, his mind was so saturated with scripture that he could barely describe what he saw without using biblical language. Scholars estimate that Revelation contains over 500 allusions to the Old Testament, though not a single direct quote. It’s as if John’s vision came to him already translated into scriptural symbols.

This would have made perfect sense to his first readers. They didn’t need commentaries to decode his meaning because they shared his scriptural vocabulary. When he wrote about:

- The tree of life (Genesis 2-3)

- The rainbow around the throne (Genesis 9, Ezekiel 1)

- Locusts like horses prepared for battle (Joel 1-2)

- The wine press of God’s wrath (Isaiah 63)

- The new heaven and new earth (Isaiah 65)

They instantly understood. These weren’t random images but carefully chosen scriptural echoes that told a coherent story: God was fulfilling all his promises, completing all his threats, answering all his people’s prayers.

Why This Matters: Scripture as Resistance Literature

For persecuted Christians, this scriptural saturation served a vital purpose. Rome could control their bodies, confiscate their property, even take their lives. But Rome couldn’t steal the scriptures written on their hearts.

When a Christian was dragged before a Roman magistrate and ordered to curse Christ, scripture gave them words: “I will bless the Lord at all times” (Psalm 34:1). When threatened with death, they remembered: “Precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of his saints” (Psalm 116:15). When tempted to despair, they recalled: “Weeping may endure for a night, but joy comes in the morning” (Psalm 30:5).

Revelation weaponized this shared memory against the empire. Every beast John described exposed Rome’s pretensions using God’s own words. Every promise of vindication drew from prophecies they’d memorized since childhood. Every vision of glory echoed songs they’d sung in hiding.

The Ultimate Reveal

This is why Revelation keeps saying “Behold!” (Look! See! Pay attention!). It’s not revealing new information but unveiling what scripture had been saying all along. The Jesus who knocked on their doors asking to come in (Revelation 3:20) was the same Jesus who’d been knocking on Israel’s door through every prophet, every psalm, every promise.

When Revelation describes Jesus with eyes like fire, feet like bronze, and a voice like rushing waters, it’s using Ezekiel’s language for God himself (Ezekiel 1, 43). When it shows Jesus receiving worship from every creature, it’s applying to him what Isaiah said belongs only to Yahweh (Isaiah 45). When it calls him “the First and the Last,” it’s using God’s own self-designation (Isaiah 44:6).

The first-century readers understood: the servant who washed their feet was the God who created their souls. The teacher who called them friends was the King who would judge their enemies. The one who died on a Roman cross was the one who would destroy Rome itself.

This is why they could face lions singing hymns. They knew how the story ended. Not because Revelation told them something new, but because it showed them that everything scripture had promised was true, and it was all about Jesus.

For them, Revelation wasn’t a puzzle about the future but a key to the present. It said: “Remember all those scriptures you’ve memorized? They’re happening now. That kingdom Daniel saw crushing all others? You’re citizens of it. That bride Isaiah described? That’s you. That victory Zechariah promised? It’s already won.”

In a world where they seemed powerless, scripture made them invincible. In a world where Caesar claimed to be lord, scripture proved Jesus was Lord. In a world where they appeared to be losing, scripture showed they’d already won.

This is the tradition Revelation culminates: not dead letters about ancient history, but living words about present reality. Not human speculation about divine mysteries, but divine revelation about human destiny. Not just comfort for the afflicted, but ammunition for the resistance.

The Word made flesh had shown them how to read the word made text. And in their darkest hour, the word made vision showed them that both pointed to the same beautiful, terrible, glorious truth: Jesus is Lord, and his kingdom is forever.

Why These Seven Churches Matter

John addressed Revelation as a letter to seven specific churches in the Roman province of Asia (western Asia Minor, modern day Turkey). In the opening lines, he greets the communities in Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea (Revelation 1:4, 11). But why these seven? Out of dozens of Christian communities scattered across the Roman world, why did the Spirit inspire John to focus on these particular congregations?

The answer lies not just in geography, but in the profound spiritual reality these churches represented. These weren’t random selections; they formed a strategic circuit along major Roman trade routes, ensuring maximum distribution of John’s message. More importantly, they embodied the full spectrum of Christian experience under persecution: faithful endurance, dangerous compromise, spiritual apathy, and everything in between. Each church served as both a mirror for first century believers and a timeless example for Christians in every era who face the same fundamental choice: conform to the world’s demands or remain faithful to Christ, regardless of the cost.

The Crushing Reality of Trade Guilds

To understand the daily pressure these Christians faced, we must grasp the stranglehold of the trade guild system; something almost entirely foreign to our modern economic experience. In the first century, virtually every profession operated through guilds: bakers, metalworkers, merchants, artisans, even tent makers like Paul. These weren’t optional professional associations; they were mandatory economic survival mechanisms.

Here’s what made them spiritually treacherous: each guild was dedicated to a patron deity and regularly held religious festivals, communal meals, and ceremonies honoring their god. Guild members were expected to participate in offerings, processions, and feasts that often included meat sacrificed to idols. Refusing to participate didn’t just mean missing a social gathering; it meant economic exile. No guild membership often meant no customers, no business partnerships, no livelihood.

Imagine a Christian silversmith in Ephesus (like those mentioned in Acts 19:24-27) trying to feed his family while his guild demanded he honor Artemis with offerings and attendance at pagan festivals. Or consider a Christian merchant in Thyatira whose textile guild required participation in ceremonies honoring Apollo. The choice was stark: compromise your faith or watch your family face poverty and social ostracism.

This is why John’s messages to the churches hit so hard. When he warned against eating “food sacrificed to idols” (Revelation 2:14, 20), he wasn’t addressing an abstract theological issue; he was speaking to Christians facing daily decisions between faithfulness and financial survival. The pressure to conform wasn’t just social; it was brutally economic.

A Letter That Traveled in Secret

John’s Apocalypse was designed as a circular letter, meant to be passed from city to city in the very order they’re listed (Revelation 1:11). Picture this: a trusted messenger, perhaps one of John’s disciples, carrying a precious scroll from Patmos back to the mainland. Under the constant threat of Roman surveillance, this letter would travel along well established trade routes, moving from congregation to congregation like a beacon of hope in the darkness.

The distribution method itself was prophetic. Each church would receive the letter, gather in secret: perhaps in a home at night or a hidden location outside town, and listen as someone read aloud John’s entire vision. “Blessed is the one who reads aloud the words of this prophecy, and blessed are those who hear and keep what is written in it” (Revelation 1:3). In an age when few Christians owned personal copies of Scripture, this communal hearing was transformative.

Imagine that oil lamp lit room in Smyrna where believers pressed in to catch every word. The reader’s voice might tremble as he conveyed John’s strange and wondrous visions, but for these listeners, this wasn’t academic speculation; it was a pastoral letter from their beloved elder, the last living apostle, giving them God’s perspective on their suffering.

Seven Cities, Seven Mirrors

Ephesus: The Church That Lost Its First Love

“I have this against you: You have forsaken the love you had at first” (Revelation 2:4)

Ephesus was the crown jewel of Asia Minor, home to one of the seven wonders of the ancient world: the temple of Artemis. This bustling commercial hub housed perhaps 300,000 people, making it the fourth largest city in the Roman Empire. The Ephesian church had an impressive pedigree: planted by Paul, nurtured by Apollos, shepherded by Timothy, and possibly pastored by John himself.

Yet success bred spiritual complacency. They had sound doctrine and could spot false teachers, but their hearts had grown cold toward Christ. How many of us recognize ourselves in Ephesus? We know our theology, we serve faithfully, we maintain moral standards, but when did we last feel that overwhelming love for Jesus that first captured our hearts?

The trade guilds in Ephesus were particularly powerful, centered around the worship of Artemis. Christian artisans faced intense pressure to participate in guild festivals and ceremonies. Some may have maintained their church attendance while slowly compromising their passionate devotion to Christ, choosing the path of least resistance rather than costly discipleship.

Smyrna: The Persecuted Church

“Do not be afraid of what you are about to suffer… Be faithful, even to the point of death, and I will give you life as your victor’s crown” (Revelation 2:10)

Smyrna (modern Izmir) was known for its loyalty to Rome and its fierce opposition to Christianity. The church there faced both Jewish opposition and Roman persecution. They were materially poor but spiritually rich; exactly the opposite of how the world measures success.

What’s remarkable about Christ’s message to Smyrna is what’s missing: no rebuke, no call to repentance, only encouragement and a promise of reward. Sometimes faithfulness looks like enduring rather than achieving, suffering rather than succeeding. The Christians in Smyrna couldn’t participate in the trade guilds without compromising their faith, so they chose poverty over apostasy.

Their example speaks to believers in every era who face genuine persecution for their faith. When following Christ costs you career advancement, social acceptance, or even your life, remember Smyrna: “Be faithful, even to the point of death.”

Pergamum: The Compromising Church

“Nevertheless, I have a few things against you: There are some among you who hold to the teaching of Balaam” (Revelation 2:14)

Pergamum served as the political capital of the province and housed multiple temples, including one of the first dedicated to emperor worship. John calls it the place “where Satan has his throne” (Revelation 2:13); likely referring to the concentration of pagan worship and imperial cult activity.

Some believers in Pergamum had found ways to participate in the economic and social life of the city while maintaining their Christian identity. They attended guild functions, ate meat sacrificed to idols, and perhaps even participated in some imperial ceremonies; all while telling themselves they didn’t really mean it in their hearts.

Their compromise reminds us of the subtle ways we can accommodate worldly values while maintaining a Christian veneer. How often do we participate in practices we know compromise our witness because it’s easier than standing out?

Thyatira: The Tolerant Church

“Nevertheless, I have this against you: You tolerate that woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophet and is teaching and misleading my servants into sexual immorality and the eating of food sacrificed to idols” (Revelation 2:20)

Thyatira was famous for its trade guilds, particularly those involving textiles and dyeing; Lydia, Paul’s first European convert, was from this city (Acts 16:14). The guilds here were especially integrated with religious practices, making it nearly impossible to participate economically without religious compromise.

The church’s sin wasn’t personal immorality but tolerance of leaders who taught that such compromise was acceptable. They had allowed a false teacher to convince them that participation in guild activities was just “cultural accommodation,” not spiritual adultery.

This speaks to churches in every age that prioritize unity over truth, tolerance over holiness. Sometimes love requires confronting sin, not overlooking it. The call to “overcome” includes overcoming false teaching within the church itself.

Sardis: The Dead Church

“Wake up! Strengthen what remains and is about to die, for I have found your deeds unfinished in the sight of my God” (Revelation 3:2)

Sardis had a reputation for being alive, but Christ declared them spiritually dead. Once a powerful kingdom, by the first century it had become a sleepy, has been city living on past glory. The church reflected its environment; they maintained the forms of Christianity while lacking its power.

Perhaps the believers in Sardis had found ways to blend so seamlessly into their culture that they no longer stood out as different. They attended church services but looked just like their pagan neighbors in their daily lives. Their faith had become culturally invisible.

How many churches today could receive the same diagnosis? We have buildings, programs, and budgets, but do we have the life transforming power of the Gospel? Are we known for our love, our holiness, our hope, or are we just another social organization?

Philadelphia: The Faithful Church

“I know your deeds. See, I have placed before you an open door that no one can shut. I know that you have little strength, yet you have kept my word and have not denied my name” (Revelation 3:8)

Like Smyrna, Philadelphia receives no rebuke from Christ; only encouragement and promise. They were a small, relatively weak congregation facing opposition from both Jewish communities and Roman authorities. Yet they had “kept Christ’s word” and “not denied His name.”

Philadelphia shows us that faithfulness isn’t measured by numerical growth or social influence but by steady obedience in the face of opposition. They had “little strength” by worldly standards, but Christ saw their faithfulness and promised to vindicate them.

Their example encourages small churches, struggling believers, and anyone who feels insignificant in the world’s eyes. God sees. God remembers. God rewards faithfulness, not just success.

Laodicea: The Lukewarm Church

“Because you are lukewarm, neither hot nor cold, I am about to spit you out of my mouth” (Revelation 3:16)

Laodicea was wealthy, comfortable, and self sufficient. The city was known for banking, textiles, and medical schools. The Christians there had apparently found ways to prosper materially while maintaining their religious identity. They needed nothing, or so they thought.

Their wealth had become their spiritual poverty. They could afford to participate in trade guilds without feeling the pinch of economic pressure. They could buy their way out of most conflicts. But prosperity had bred spiritual apathy.

Christ’s message to Laodicea is perhaps the most sobering in all seven letters because it addresses the subtlest and most dangerous form of spiritual compromise: not outright denial of faith, but gradual cooling of passion for Christ. They weren’t hot with devotion or cold with rejection; they were lukewarm with indifference.

Timeless Mirrors for Every Generation

These seven churches weren’t chosen arbitrarily; they represent the full spectrum of Christian experience across time. In every era, believers face the same fundamental challenges: persecution that tests our courage, prosperity that tests our dependence on God, false teaching that tests our discernment, and cultural pressure that tests our willingness to be different.

The beauty of John’s circular letter is that each church could learn not only from their own specific message but from all seven. The faithful church in Smyrna could be encouraged by Philadelphia’s promise of vindication. The compromising church in Pergamum could be warned by Sardis’s spiritual death. The prosperous church in Laodicea could be challenged by Smyrna’s willing poverty for Christ’s sake.

A Message of Ultimate Hope

Despite the varied conditions of these churches (some faithful, some compromising, some dying), John’s overarching message is one of hope. To each church, Christ gives the same promise: “To the one who is victorious…” (Revelation 2:7, 11, 17, 26; 3:5, 12, 21). Victory isn’t guaranteed by our circumstances but by Christ’s power working in and through us.

The Christians facing trade guild pressure in Thyatira needed to hear that there was a way to overcome without compromise. The believers facing persecution in Smyrna needed to know that their suffering had meaning and their faithfulness would be rewarded. The lukewarm church in Laodicea needed to understand that Christ was still knocking at their door, still offering fellowship with those who would open to Him.

As you read about these seven churches, ask yourself: Which one mirrors my current spiritual condition? What is Christ saying to me through their examples? The same Jesus who walked among the lampstands in John’s vision walks among His churches today, seeing everything, knowing everything, calling each of us to overcome by His grace and power.

The message that traveled secretly from church to church in first century Asia Minor still travels today: Christ is victorious, His people will overcome, and no earthly power (whether Roman emperors or trade guilds or cultural pressure) can ultimately prevail against those who remain faithful to the Lamb who was slain but now lives forever.

“Whoever has ears, let them hear what the Spirit says to the churches” (Revelation 2:7, 11, 17, 29; 3:6, 13, 22).”

(Read more → The Strategic Circuit: How Revelation Spread Along Roman Trade Routes → The Stranglehold of Trade Guilds: Economic Warfare Against Faith → The Seven Churches: A Call to Overcome Through Repentance)

The Trinity of Temptation: Decoding Humanity's Ancient Enemies

When John composed Revelation, he wasn’t creating new symbols from thin air. He was drawing from a treasure trove of Old Testament imagery that his first-century audience knew by heart. The Book of Revelation contains no formal quotations from the Old Testament, but includes no fewer than 620 allusions meaning there is approximately a 2:1 ratio of Old Testament allusions to verses in Revelation . John’s apocalyptic vision masterfully weaves together ancient prophetic imagery to reveal the three great enemies every believer faces: the world, the flesh, and Satan.

The World: The Beast System’s Total Domination

The Beast from the Sea: Political and Military Power

John’s description of the beast rising from the sea provides a terrifying portrait of worldly power: “And I saw a beast rising out of the sea, with ten horns and seven heads, with ten diadems on its horns and blasphemous names on its heads. And the beast that I saw was like a leopard; its feet were like a bear’s, and its mouth was like a lion’s mouth” (Rev. 13:1-2).

For first-century Christians, this composite creature was immediately recognizable. The beast combined features from Daniel’s four beasts (Daniel 7:1-8), which represented successive world empires: Babylon (lion), Medo-Persia (bear), Greece (leopard), and Rome (the fourth, terrible beast). John’s sea beast embodied all previous worldly powers, suggesting Rome was the culmination of human rebellion against God’s kingdom.

The seven heads represented Rome’s seven hills, making the identification unmistakable to any Roman citizen. But they also symbolized the succession of Roman emperors who had claimed divine status. The ten horns with crowns represented Rome’s client kingdoms and provinces that extended the empire’s reach. The “blasphemous names” on its heads directly referenced the divine titles Roman emperors claimed: “Lord and God,” “Savior of the World,” “Son of God” titles that belonged to Christ alone.

The beast’s emergence from the sea was particularly significant. In Jewish apocalyptic literature, the sea represented chaos, the unknown, and the realm of evil. For Christians in Asia Minor, this image evoked Rome’s naval conquests that brought foreign domination across the Mediterranean. The beast didn’t just represent political power; it embodied the worldly system that promised security and prosperity through human achievement rather than divine providence.

The Beast from the Earth: Religious and Cultural Power

The second beast completes the worldly system: “Then I saw a second beast, coming out of the earth. It had two horns like a lamb, but it spoke like a dragon” (Rev. 13:11). Later, John identifies this as “the false prophet” (Rev. 16:13, 19:20, 20:10). While the sea beast represented Rome’s political and military dominance, the earth beast represented its religious and cultural propaganda machine.

This beast from the earth perfectly described the imperial cult that presented itself as benevolent while serving the dragon’s purposes. The “two horns like a lamb” suggested religious authority and peaceful intentions, but it “spoke like a dragon,” revealing its true allegiance. For first-century Christians, this represented the local priesthood of the imperial cult, particularly the provincial councils in Asia Minor that enforced emperor worship through religious ceremonies rather than military force.

The earth beast’s power was more subtle but equally dangerous. It didn’t conquer through armies but through cultural persuasion, religious justification, and economic incentive. It “performed great signs” (Rev. 13:13), including making “fire come down from heaven,” which first-century readers would have recognized as the elaborate theatrical effects used in imperial cult ceremonies. Hidden mechanisms, mirrors, and other devices created the illusion of miraculous powers that validated the emperor’s divine claims.

The Mark of the Beast: Economic Control

The two beasts worked together to create a totalitarian worldly system. The earth beast “forced all people, great and small, rich and poor, free and slave, to receive a mark on their right hands or on their foreheads, so that they could not buy or sell unless they had the mark” (Rev. 13:16-17).

For first-century Christians, this wasn’t futuristic technology but the immediate reality of the guild system in Roman cities. Trades and businesses were organized into guilds that required members to participate in ceremonies honoring the guild’s patron deity and the emperor. The “mark” represented the certificates, tokens, or other proof of participation that guild members needed to conduct business legally.

Christians who refused to participate in these religious-economic ceremonies found themselves excluded from professional life, unable to practice their trades, and cut off from the commercial networks that sustained Roman urban life. The worldly system demanded total allegiance: political submission to the sea beast and religious participation through the earth beast.

The Complete Worldly System

Together, these two beasts represented the world as a complete system opposing God’s kingdom. The sea beast provided the political structure, military power, and governmental authority that promised security and order. The earth beast provided the religious validation, cultural justification, and economic incentives that made the system appear not just necessary but desirable.

First-century Christians understood that they weren’t just facing individual temptations but a comprehensive worldly system designed to replace their allegiance to Christ. The world didn’t just offer alternative pleasures; it offered an alternative kingdom with its own savior (Caesar), its own gospel (Roman peace and prosperity), its own priesthood (imperial cult), and its own economic system (guild membership).

Modern believers face the same complete worldly system through different manifestations. Contemporary political systems promise security through human government rather than divine providence. Cultural institutions provide religious-sounding justification for values that oppose biblical truth. Economic systems demand participation in practices that conflict with Christian ethics. Together, they create a comprehensive alternative to God’s kingdom that appears both necessary and beneficial.

The Flesh: Babylon’s Luxurious Seduction

The Great Prostitute: Sensual Desires and Material Compromise

When John describes the great prostitute sitting on seven hills, adorned with purple, scarlet, gold, and precious stones (Revelation 17:1-6), he reveals the flesh’s seductive power through imagery that appeals directly to human desires. The prostitute represents not just Rome’s materialism but the flesh’s craving for luxury, pleasure, and sensual satisfaction.

Just as a prostitute offers pleasure in exchange for money, the flesh offers immediate gratification in exchange for spiritual compromise. The prostitute’s luxury “purple and scarlet” clothing, “gold, precious stones and pearls” represented not just Rome’s wealth but the flesh’s desire for beautiful things, expensive possessions, and social status. Purple dye was so expensive that only the elite could afford it, making it the ultimate symbol of the flesh’s craving for exclusivity and prestige.

This imagery wasn’t new. The Old Testament prophets regularly portrayed unfaithful cities like Tyre and Nineveh as prostitutes for their commercial exploitation and sensual indulgence. Ezekiel 16 describes Jerusalem as an unfaithful wife who became a prostitute, trading her covenant relationship with God for material pleasures and worldly alliances. The prostitute imagery throughout Scripture consistently represents the flesh’s tendency to seek satisfaction through sensual pleasure rather than spiritual relationship.

The Prostitute Riding the Beast: Flesh Exploiting Worldly Power

The crucial detail that the prostitute “rides the beast” (Rev. 17:3) reveals how the flesh exploits worldly systems for personal gratification. For first-century Christians, this image showed how Rome’s citizens enjoyed luxury that literally rode on the back of the empire’s military conquests and political oppression. The flesh always seeks to benefit from worldly power while remaining comfortable and seemingly innocent.

The prostitute didn’t create the beast’s violence, but she certainly enjoyed its benefits. Roman citizens lived in comfort because their armies conquered other peoples. They ate exotic foods because their trade networks exploited distant lands. They wore expensive clothing because their economic system concentrated wealth through systematic oppression. The flesh loves to enjoy the benefits of worldly systems while maintaining plausible deniability about their methods.

This pattern continues today. The flesh seeks the benefits of economic systems while ignoring their exploitative practices, enjoys products while remaining willfully ignorant of their production methods, and pursues comfort while avoiding responsibility for its consequences. The prostitute represents the flesh’s desire to have pleasure without paying its true cost.

Drunk with Luxury and Violence

John describes the prostitute as holding “a golden cup full of abominations and the filth of her adulteries” and being “drunk with the blood of God’s holy people” (Rev. 17:4-6). This imagery reveals how the flesh becomes intoxicated with both luxury and violence, losing moral sensitivity through constant indulgence.

For first-century Christians, this described how Roman luxury culture had become desensitized to the suffering that sustained it. Citizens attended gladiatorial games where human beings were slaughtered for entertainment. They enjoyed elaborate feasts while slaves served them. They wore jewelry made from wealth extracted through conquest and oppression. The flesh, intoxicated by pleasure, gradually loses its capacity for moral judgment and compassion.

The golden cup filled with abominations represents how the flesh packages its desires in attractive forms. The cup is beautiful, but its contents are spiritually toxic. The flesh presents its cravings as sophisticated pleasures, refined tastes, and cultural experiences while hiding their destructive spiritual effects.

The Merchants of Souls and Professional Ambition

Revelation 18:12-13 provides a devastating inventory of luxury trade that concludes with “human beings sold as slaves,” revealing how the flesh’s desires ultimately commodify people. The flesh’s pursuit of success, status, and material pleasure inevitably exploits others and treats relationships as means to personal ends.

This connects directly to the trade guilds that required Christians to compromise their faith for professional advancement. The guilds represented the flesh’s desire for career success, financial security, and social recognition. Guild membership offered economic opportunity, professional networking, and elevated social status for those willing to participate in ceremonies honoring patron deities and the emperor.

For a Christian craftsman, refusing guild membership meant rejecting the flesh’s promise of professional success. The flesh rationalized: “It’s just business. Everyone does it. How can I provide for my family if I don’t advance professionally? God wants me to be successful, doesn’t He? These ceremonies are just cultural traditions, not real spiritual compromise.”

The guild feasts weren’t merely ceremonial; they were strategic career moves that appealed directly to fleshly desires. These elaborate gatherings featured fine food, wine, and entertainment that satisfied the flesh’s craving for pleasure while providing opportunities to meet influential clients, negotiate lucrative contracts, and demonstrate commitment to professional advancement.

The False Prophet’s Appeal to Fleshly Desires

The beast from the earth, identified as “the false prophet,” worked through the imperial cult to provide religious justification for fleshly compromise. The false prophet didn’t just enforce emperor worship through threats; it provided sophisticated theological accommodation for people’s desire to hear what their itching ears wanted to hear.

Paul warned Timothy about this tendency: “For the time will come when people will not put up with sound doctrine. Instead, to suit their own desires, they will gather around them a great number of teachers to tell them what their itching ears want to hear” (2 Timothy 4:3). The imperial cult’s false prophets provided exactly this service, offering religious teachings that accommodated people’s fleshly desires while maintaining a veneer of spirituality.

Imperial cult priests taught that honoring Caesar was compatible with honoring other gods, that business success was a sign of divine favor, and that participating in guild activities was civic virtue rather than spiritual compromise. They transformed worldly ambition into religious duty and presented career advancement as stewardship of God-given talents.

Modern Manifestations of Fleshly Indulgence

Today’s manifestation of the prostitute appears in consumer culture that promises fulfillment through acquisition, entertainment industry that offers pleasure without consequence, and social media that feeds the flesh’s craving for recognition and validation. Like ancient Rome, modern culture packages fleshly desires in attractive forms while hiding their spiritual toxicity.

The flesh continues to seek religious justification for its desires through teachers who accommodate rather than challenge. Contemporary false prophets tell people that God wants everyone wealthy, that personal ambition is always blessed, that biblical principles should bend to accommodate career opportunities, and that spiritual maturity means embracing cultural values rather than challenging them.

Modern believers face the same guild-like pressures through professional associations, corporate cultures, and industry standards that demand compromise in exchange for advancement. The flesh whispers that we can pursue worldly success without spiritual consequence, that our identity comes from our achievements, and that biblical standards are outdated restrictions rather than protective boundaries.

Satan: The Dragon’s Spiritual Warfare

The Ancient Serpent’s Relentless Pursuit

Revelation 12 presents Satan as “the great dragon… that ancient serpent called the devil, or Satan, who leads the whole world astray” (Rev. 12:9). This imagery draws directly from Genesis 3, where the serpent deceived Eve, and Isaiah 27:1, which speaks of God punishing “Leviathan the fleeing serpent, Leviathan the coiling serpent”.

For first-century Christians, the dragon chasing the woman (Revelation 12:13-17) represented their daily experience of spiritual warfare. This wasn’t abstract theology but practical reality. Satan’s attacks came through multiple channels: imperial persecution that threatened their lives, false teachers who infiltrated their churches, demonic activity that opposed their prayers and worship, and spiritual deception that confused their understanding of truth.

The dragon’s pursuit was relentless and personal. While the beasts represented the worldly system and the prostitute represented fleshly desires, the dragon represented the supernatural intelligence actively orchestrating both. First-century Christians faced demonic opposition through occult practices embedded in Roman culture, spiritual intimidation during times of persecution, and supernatural deception that made distinguishing truth from falsehood increasingly difficult.

The Accuser’s Daily Strategy

Satan’s primary weapon against believers was accusation: “the accuser of our brothers and sisters, who accuses them before our God day and night” (Rev. 12:10). For first-century Christians facing persecution, these accusations were intensely personal and practically devastating.

The dragon whispered: “You’re not strong enough to endure persecution.” “God has abandoned you in your suffering.” “Your faith isn’t real if you’re struggling with doubt.” “You’ve compromised too much already there’s no point in standing firm now.” “Other Christians are more faithful than you.” “Your prayers aren’t answered because of your failures.” “God is disappointed in your lack of courage.”

These accusations intensified during times of trial. When Christians faced the choice between burning incense to Caesar or facing imprisonment, torture, or death, Satan amplified their fears, magnified their doubts, and highlighted their past failures. The dragon’s strategy was to isolate believers from God’s love and from each other through shame, condemnation, and despair.

The Dragon’s Authority Behind the Beasts

Revelation 13:2 reveals that “the dragon gave the beast his power and his throne and great authority.” Satan didn’t just oppose Christians directly; he worked through worldly systems and fleshly desires to accomplish his purposes. The dragon was the unseen power behind both the beast’s political oppression and the prostitute’s seductive luxury.

This explains why spiritual warfare isn’t just about resisting obvious temptations but about recognizing the demonic intelligence behind worldly systems and fleshly desires. The dragon used Rome’s political power to persecute Christians, imperial cult religion to provide false spiritual alternatives, economic pressure to force compromise, and cultural luxury to seduce believers away from faithful living.

Supernatural Opposition to Church Life

The dragon’s warfare targeted Christian communities directly. First-century churches experienced supernatural opposition through false prophets who claimed divine revelation while leading people away from Christ, demonic activity that disrupted worship and prayer meetings, spiritual confusion that created division and conflict within congregations, and occult practices from their pagan backgrounds that continued to influence new converts.

Satan’s attacks were sophisticated and multifaceted. He didn’t just use obvious opposition like Roman persecution; he infiltrated churches through false teaching, stirred up personality conflicts between leaders, exploited cultural divisions between Jewish and Gentile Christians, and used the pressure of economic hardship to create resentment and division within congregations.

The dragon’s ultimate goal was to prevent the church from fulfilling its mission. If he couldn’t destroy Christians through persecution, he would corrupt them through compromise. If he couldn’t silence the gospel through threats, he would confuse it through false teaching. If he couldn’t eliminate Christian communities through external pressure, he would divide them through internal conflict.

Modern Spiritual Warfare

Contemporary believers face the same draconic opposition through different methods. Satan continues his work as accuser, convincing Christians they’re not good enough, smart enough, or faithful enough for God to use them. He promotes spiritual discouragement through comparison with other believers, guilt over past failures, and fear about future challenges.

The dragon’s modern strategy includes promoting biblical illiteracy that leaves Christians vulnerable to false teaching, fostering spiritual pride that creates division within churches, encouraging busyness that crowds out prayer and Bible study, and supporting cultural pressures that make Christians ashamed of their faith.

Just as first-century Christians faced supernatural opposition to their church life, modern believers encounter spiritual warfare through attacks on their prayer lives, confusion about biblical truth, division within their congregations, and demonic influence through entertainment, relationships, and cultural values that oppose God’s kingdom.

The Slain Lamb: Victory Over All Three Enemies

The Ultimate Overcomer

At the center of Revelation stands not a conquering warrior but “a Lamb, looking as if it had been slain” (Rev. 5:6). This paradoxical image strength through sacrifice, victory through death reveals how Christ defeated the world, flesh, and Satan.

Against the world’s beastly system: Jesus declared, “In this world you will have trouble. But take heart! I have overcome the world” (John 16:33). The Lamb’s blood purchases people “from every tribe and language and people and nation” (Rev. 5:9), creating a kingdom not built on political oppression or religious manipulation but on sacrificial love. Christ’s victory over the world means believers don’t need to find security through worldly systems or validation through cultural acceptance.

Against the flesh’s seductive desires: The Lamb who was slain demonstrates true satisfaction through service, not self-indulgence. “Worthy is the Lamb, who was slain, to receive power and wealth and wisdom and strength and honor and glory and praise!” (Rev. 5:12). True fulfillment flows from humble service and spiritual relationship, not material pleasure or professional achievement. Christ’s victory over the flesh means believers can find satisfaction in God rather than through sensual gratification or worldly success.

Against Satan’s accusations: The dragon may be “the accuser of our brothers and sisters, who accuses them before our God day and night” (Rev. 12:10), but he “has been hurled down” by the Lamb’s blood. Christ’s sacrifice silences every accusation and breaks every chain of spiritual bondage. The Lamb’s victory over Satan means believers can stand confident in their relationship with God despite their failures and weaknesses.

The Timeless Battle, The Eternal Victory

Revelation contains Old Testament allusions in almost every verse , creating a tapestry that first-century Christians could immediately recognize. The three enemies John portrayed the world’s beastly system, the flesh’s prostitute-like seduction, and Satan’s draconic warfare mirror the same temptations Jesus faced in the wilderness (Luke 4:1-13) and that believers face today.

Yet Revelation’s ultimate message isn’t about the enemies’ power but about their defeat. The beast, the false prophet, and the dragon are all thrown into the lake of fire (Rev. 20:10). The prostitute’s luxury becomes mourning (Rev. 18:9-19). The accuser is silenced forever.

For first-century Christians facing persecution, economic pressure, and demonic opposition, this wasn’t abstract theology it was survival. The same symbols that helped them decode their political reality also revealed their spiritual victory. The Lamb who was slain had already won the war they were fighting daily.

For modern believers, these ancient symbols retain their power. Whether we face the world’s systematic opposition, the flesh’s seductive desires, or Satan’s accusations, the message remains unchanged: “They triumphed over him by the blood of the Lamb”. The victory is already won; we simply need to walk in it.

The Unbreakable Faith: Why First-Century Christians Chose Death Over Denial

To those first-century Christians, Revelation was far more than a catalog of symbols – it was a pastoral letter of encouragement in a time of tribulation [s]. John identifies himself as their “brother and companion in the suffering and kingdom and patient endurance that are ours in Jesus” (Rev. 1:9). That phrase alone signaled the book’s purpose: to strengthen patience and endurance. The believers hearing it were weary and anxious. Some had seen friends jailed or even killed. Others were exhausted by constant social pressure; temptations to give in and join the crowd in pagan festivals just to avoid sticking out. Revelation acknowledges these very human feelings of fear, sorrow, and temptation, then speaks directly to them with divine comfort. Over and over, the message is “hold on; God sees your tears, and He has a glorious reward in store if you overcome.”